Mentoring - theory and practice

Section outline

-

Welcome

to this short, applied course for individual learners, and applicable for mentors or mentees within the Peoples-Praxis capacity building programme.

⏱ 60mins 🧭 Self-paced

Gain a certificateWho it’s for

Anyone in public health (and allied roles) who is starting or refreshing their mentoring.

Course aims

Review the theory of mentorship and to help guide the process.

How it works

- Work through course content online.

- Self-paced learning and activities.

- Post to each forum and download files to receive a Certificate of completion.

Navigation tips

- Work through the topics on this page

- Download resource documents and post to the forums to receive a certificate

- To check your progress towards course completion and a certificate, view the block on the right hand side of this page

About the course

- The course has been developed by Peoples-Praxis, which offers mentorship and online courses for those in public health and related fields

- The principles and practice of mentorship should be relevant across many professional areas

Note: if you want to gain a certificate for completing this course, you will have to create an account and log in as a student.

A quote from The Science of Mentoring Relationships: What Is Mentorship? might be a good way to introduce this course:

'Over the past two decades, a paradigm shift has led to reframing mentoring relationships as definable, reciprocal, and dynamic. According to this new framing, effective mentoring requires complex skills that can be taught, practiced, and mastered, and it accrues measurable benefits for mentees and mentors. Mentoring relationships are now seen as collaborative processes in which mentees and mentors take part in reciprocal and dynamic activities such as planning, acting, reflecting, questioning, and problem solving.'

This is backed up by a quote from Ten simple rules for establishing a mentorship programme:

'Mentoring has traditionally been defined as a method of professional and personal development where a person with expertise in a particular field or area of research (the mentor) advises and guides someone (the mentee) in that particular area or on specific skills. Based on research over the past 20 years, the understanding of mentoring has evolved and it is now seen as a complex, collaborative, interactive process that may include more than 2 people.'Terminology can be confusing, and there may be overlap between mentoring, supervision, coaching or training. Mentor can be a noun - a person who is a trusted advisor, or a verb - to advise or train someone. A mentee is someone who is advised or trained by someone else - their mentor.A statement from the Peoples-Praxis website sums up an important approach: 'The Mentoring process should be led by the needs of the mentees. Both mentees and mentors should be committed and willing to make the time for the partnership between them. The relationship is reciprocal, both parties gaining from it and being open minded and ready to change.'Mentorship need not be confined to a one-on-one relationship, but can include a collaborative group process, as in the quote above. Again in the context of Peoples-Praxis, we see the possibility of mentors guiding a group of mentees through one of the courses on this site.Ways to navigate the course: Click on the hyperlinks to take you to a set of resources in each section. There is also a place for reflection - you can either reflect on your own, or join the forum to put your views and respond to those of others.

Note: you can earn a Certificate if you access the resources and post a reflection in each Topic.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

-

In the Introduction to this course we quoted from a chapter by the National Academy of Sciences from The Science of Mentoring Relationships: What Is Mentorship?. The chapter is an important read, and identifies the two main features - psychosocial support and career development support:

'Mentorship is a professional, working alliance in which individuals work together over time to support the personal and professional growth, development, and success of the relational partners through the provision of career and psychosocial support.'

Strong mentoring feels like a strong working alliance: mentor and mentee set clear goals together, agree tasks, and build a bond of trust.

Career support

- Practical guidance and skills development

- Introductions and networking

- Sponsorship where appropriate

Psychosocial support

- Encouragement and active listening

- Positive role-modelling

This table from the chapter lists the various mentorship functions - when you read the chapter itself you will see that the table also list the source of each of the functions:

Related Behaviors and Activities

Psychosocial Support

Psychological and emotional support

Mentor encourages mentees, helps with problem solving, and uses active-listening techniques.

Role modeling

Mentor serves as a guide for mentees' behavior, values, and attitudes. Mentees benefit from engaging with mentor who shares values and deep-level similarity with them. Allows mentees to see themselves as future academics.

Career (Instrumental) Support

Career guidance

Mentor provides support for assessing and choosing an academic and career path by evaluating mentees' strengths, weaknesses, interests, and abilities. Mentor's role includes

-

helping mentees reflect and think critically about goals;

-

facilitating mentees' reflection on and exploration of their interests, abilities, beliefs, and ideas;

-

reviewing mentees' progress toward goals;

-

challenging mentees' decisions or avoidance of decisions; and

-

helping mentees to realize their professional aspirations.

Skill development

Mentor educates, evaluates, and challenges mentees academically and professionally; tutors or provides training; and focuses on subject learning.

Sponsorship

Mentor publicly acknowledges the achievements of mentees and advocates for mentees.

The chapter also lists a variety of mentoring relationships:

'Mentoring relationships can occur in formal, structured, and intentional settings or as informal, organically developed relationships—sometimes structured, sometimes not—that a mentee develops with a more experienced individual with whom the mentee has regular contact (Inzer and Crawford, 2005). Mentoring relationship structures can include the following:

-

A single mentor working with a single mentee in a classic dyadic relationship

-

A group of mentors sharing their collective wisdom with one mentee

-

One mentor working with multiple mentees

-

Peer and near-peer mentoring structures

-

Online peer communities

-

Programmatic mentoring

-

Mentoring experiences delivered through carefully constructed short-term seminars, workshops, or presentations'

For those with an interest in the theory of mentorship, there is more information in the chapter. However, for now, this sets the scene for further discussion of how to be a good mentor.AI has produced this graphic about what mentoring is and isn't:

-

Please reflect on the information in this section on the science of mentoring. Which aspect do you recognise as relevant to your personal interest in mentoring?

-

What Makes Mentoring Effective?

The blog from the Chronicle of Evidence Based Mentoring suggests 5 features of highly effective mentoring relationships.

They are:

1. The Alliance: 'the working relationship and partnership that is forged between a mentor and mentee...the alliance consists of three components: the bond that is forged, agreement on the goals, and agreement on the specific tasks and activities that will be undertaken to achieve those goals. The alliance builds on initial trust and positive expectations from both parties to create a collaborative, purposeful bond centered around the common goals and tasks of the intervention.'

2. Empathy and Related Constructs: 'empathy is “a complex process by which an individual can be affected by and share the emotional state of another, assess the reasons for another’s state, and identify with the other by adopting his or her perspective.” This implies not just sensing another’s feelings and emotions but understanding and and seeing things from their perspective.'

Attunement: 'Related to this concept is attunement, or mentors’ ability to read and attend to the needs of their mentees.'

Positive Regard: 'The distant cousin of empathy and attunement, positive regard, constitutes another common factor in good relationships...positive regard [is] not only noticing but expressing appreciation for another’s positive attributes.'

Genuineness: 'Another related construct is genuineness, or the sense that the mentor is being authentic.'

3. Positive Relationship Expectations: 'Mentees and mentors both need to have expectations that their work will be successful – something that is not always appreciated in mentoring programs.'

4. Cultural Adaptations: 'mentoring...emerged from the dominant cultural groups within North America and Western Europe. As such, how mentees’ problems and solutions are framed, and even the ritual of one-on-one meetings, may not always align with the values and perspectives of ethnic and racial minority groups.'5. Mentor Skills and Experience: 'perhaps not every volunteer has the capacity to be a mentor...Mentors also need to be open to learning not just from the program but from their mentees, and willing to ask for advice when they need it...mentors should be open and willing to get the support they need from their programs and avoid an overly prescriptive, heavy-handed, or rigid mentoring approach.'And a possible 6th: Homework and Practice: 'A common factor that is not enumerated in traditional therapy literature, but which has emerged in recent years is homework or activities that the mentee can work on between sessions.'

Below we switch to a slightly different topic - that of how can mentees best benefit from the mentoring process:

Mentorability - the ability of mentees to benefit from mentoring

The concept of mentorability has emerged 'The key to mentorability is an open and reciprocal partnership between mentor and mentee'. The TED Talk blog Are you mentorable? discusses the principal characteristics of mentorability.

1. You understand the value of their time.

2. You’re clear about what you’re looking for from a mentor.

3. You can accept input, advice and — sometimes — criticism.

4. For the lifespan of your relationship, you keep asking, “Am I a good mentee?”

5. You’re open to whatever you can learn from your mentor.

If you have 11 minutes, you can see on a YouTube presentation how Victoria Black says No One is Talking to the Mentees:

.-

Reflect on whether you think that you would make a good mentor or a good mentee yourself

-

-

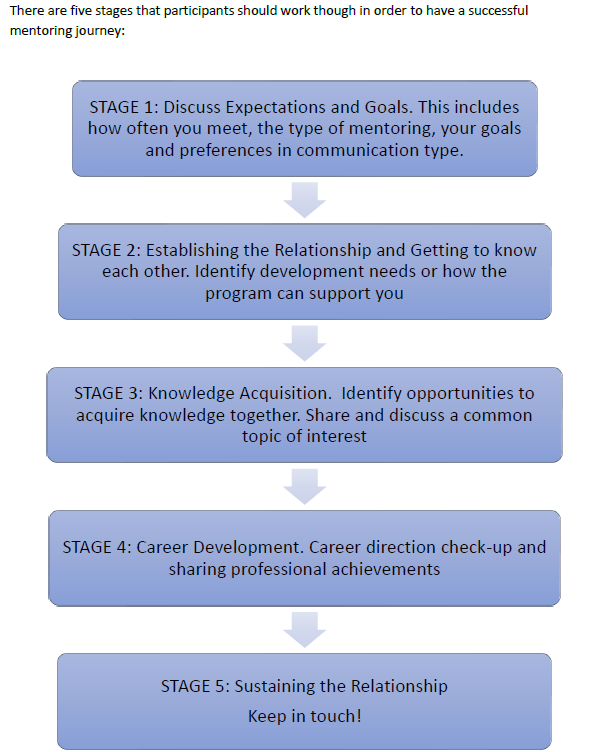

There are many guides to mentoring. Many of the important steps have been covered in earlier parts of the course. Here is a simple 5-step process for the mentoring journey - from CAPHIA.

In the African context, the African Academy of Sciences has a guide to effective mentoring. It starts: 'In developmental mentoring models, mentees are expected to be on the driving seat and autonomous in goal setting while their mentors encourage and support their learning and growth. There is no line of accountability, but both partners should learn from the mentoring relationship. The following strategies should enhance efficiency in your mentoring relationship':

Developing mentorship goals; The mentoring agreement; Your first meeting; Structuring mentoring sessions; and concludes: Effective relationships: A successful mentoring relationship depends on establishing and nurturing friendly, encouraging and supportive mentor-mentee interactions. You can read the details again in the file here.

Of course all this comes after the selection of mentors and mentees and identification of the communication platform etc.

-

Reflect on which of the practical issues we have missed in this short course

-

-

Although much of what is in this section of the course is relevant to all mentor and mentee relationships, there may be some special issues in low- to middle-income settings:

Mentoring traditions

- There may not be a strong tradition of mentoring

- Much of the evidence base has come from high-income countries were cultural settings may be different

Leadership

- Mentorship is inarguably crucial for nurturing future global health leaders

- The colonial mindset must be changed to reduce the inequities in global health leadership

In the paper Strengthening Mentoring in Low- and Middle-Income Countries to Advance Global Health Research: An Overview, the authors define 'Mentorship is the professional relationship by which the mentor, “an experienced and highly regarded, emphatic person,” guides a more junior colleague, the mentee, in developing and reassessing his/her ideas, learning and development, and substantially furthers his/her personal and professional growth'

and they state 'Many LMIC institutions do not yet have a strong tradition of mentoring, mentoring programs are very uncommon, very few LMIC scientists have received mentorship training, and institutions lack the resources and capacities needed to institutionalize mentoring programs and processes. Also, existing evidence, best practices, and norms for successful mentoring are not fit to LMICs but instead are highly biased toward the environments and resources of high-income countries, where opportunities abound and a diverse array of professionals with different backgrounds are trained, prepared, supported, and often rewarded to serve as mentors.'

The authors conclude: 'The advancement of global health research demands sustained career development opportunities for LMIC scientists that can only be attained via the implementation and dissemination of culturally compatible mentoring practices. Institutional resources and local academic and cultural factors should guide the phased implementation of tailored mentoring activities and programs for each setting, with planned, periodic evaluation of progress. Low- and middle-income country institutions also need to support existing mentors and train additional ones, while mentees can contribute to prevent overburdening the few trained mentors available, by playing an active role in the operational efforts of mentoring programs via progressing and peer mentoring. We hope this special issue will become part of the foundation of LMIC-specific mentoring approaches around the globe.' And of course this will be similar in other areas, nit just global health research.

Mentoring for leadership.In the paper A new path to mentorship for emerging global health leaders in low-income and middle-income countries, the authors say 'Evidence strongly suggests that mentorship is inarguably crucial for nurturing future global health leaders. This can be particularly challenging when there are considerably fewer leaders from LMICs due to the existing inequities in global health leadership...Current narratives on equitable partnerships mostly include academics and practitioners based in HICs who have focused on assuming responsibility for mentoring their LMIC partners...To truly shift power, LMIC collaborators must take ownership and identify context specific and nuanced skill sets needed for mentors and mentees. This is one of the few sustainable approaches to end dependency on HICs for training of our global health professionals and scientists...The major challenge to shift the local power imbalance is that power structures within global health have (un)intentionally produced leaders in LMICs with a similar colonial mindset to that seen in HICs, which reinforces power being concentrated in few hands, including mentorship of future leaders. For example, current leaders who attract the most funding gain control over international grants that results in substantial power over their institutions. This is compounded by complex systems that have created barriers such as hierarchy, bureaucracy, and capacity, limiting mentorship opportunities.A large-scale study of thousands of scientists around the world found that “mentees achieved the highest impact when they displayed intellectual independence from their mentors and did their best work when they break from their mentors’ research topics”. For mentees in LMICs to achieve such an impact, the process will have to entail allowing them to follow an independent track with structured pathways in place. Mentorship hence becomes a pivotal part of the larger succession planning in global health.We conclude that there is a dire need to mentor investigators in LMICs to reduce inequities in global health leadership. If left as is, we will continue to perpetuate the same cycle of inequities, where privileged mentees become global health leaders driving the development of a cadre of professionals who are stuck in the same role, and unable to advance their career to contribute to the field meaningfully.'The authors offer a number of recommendations to strengthen mentorship for emerging leaders in LMICs - relating to the institutions, the mentees themselves, funders and journals, and national bioethics committees. You can see the details in the paper here or as a pdf file below.A further paper titled Human-centred mentorship in global health research: are we ready to give what it takes? offers a related perspective. 'Human-centred approach is characterised by ‘valuing empathy and relationship building between the mentor and the mentee built on equitable sharing of power and shedding of privilege within hierarchical structures’. A summary of the key points is as follows:

-

Human-centred mentoring has been suggested as a sustainable strategy to nurture emerging leaders in low-income and middle-income countries for equitable and diverse representation in global health.

-

Building on the argument that investigators in these countries need to take responsibility, we take a deeper dive into the challenges of implementing this approach aimed at developing independent leaders.

-

The current global health environment where power is concentrated with few individuals hinders any progress towards institutional level changes to promote such practices. Moreover, such an environment also prematurely rewards mentees who may be resistant to this alternative form of mentoring.

-

A transformative mentorship relationship which is anchored in trust, respect, meaningful relationships and problem sharing with due responsibilities for both mentors and mentees can help create willingness in mentees to be trained as individuals ready to take on an independent path.

Guidelines for mentees include: Choosing a mentor; Familiarisation with the research culture; Continuous learning, constructive feedback and teamwork is the key; Values over skills.You can read these guidelines in full in the paper here and in the pdf version below.-

Reflect on the main barriers to effective mentorship in LMICs

-

Mentoring, Supervision, and Coaching

Terminology can be confusing, and the words mentoring, supervision, and coaching are often used interchangeably. There is some overlap (and you can blend approaches), but here are the core differences and when to use each.

Mentoring — Grow the person

Definition: Broad career & identity development with role-modelling and, where appropriate, sponsorship/networking. Longer-term, mentee-led, reflective.

Choose when: You want to grow into a new scope/identity, build networks, and translate learning into practice over months.

Short example

You’re a junior public health officer aiming to lead community engagement in 12 months. Your mentor helps you map stakeholders, shadow key meetings, and practice a 3-minute advocacy pitch. You meet monthly and keep a one-page update.

Supervision — Assure the work

Definition: Standards, governance, and accountability with documented learner/professional progression. Supervisor holds formal responsibility/authority.

Choose when: There’s risk, regulation, or assessed competence (e.g., incidents, protocols, sign-off for progression).

Short example

After an outreach clinic, a data-quality issue is found. Your supervisor reviews the incident against policy, sets corrective actions, captures learning, and signs off competence once standards are met.

Coaching — Achieve a goal

Definition: Focused, time-bound series (often 2–6 sessions) to reach a performance or leadership goal, using structured tools and rehearsal.

Choose when: You must perform a task soon (presentation, negotiation, difficult conversation) or build a specific behaviour.

Short example

You’re presenting a vaccine-uptake plan next week. A coach runs two rehearsals (e.g., GROW): sharpen the key message, practice delivery, agree adjustments, and set a rehearsal schedule.

🔑 Key Differences At a glance

Dimension Mentoring Supervision Coaching Primary focus Growth, identity, navigation, opportunities Safety, standards, compliance, progression Specific performance/leadership goal Time horizon Medium–long term (months) As required by policy/rotation Short, fixed series (weeks) Who leads Mentee leads agenda; mentor supports Supervisor directs; formal authority Coach structures sessions & tools Accountability Gentle accountability; reflective evidence Formal accountability; records & sign-off Task/behaviour change; session outcomes Typical outputs Stakeholder maps, networking, PDP, portfolio Compliance logs, incident reviews, competency sign-off Rehearsal plans, action lists, skill checklists Common tools One-page updates, reflective prompts Policies, standards, governance templates GROW, CLEAR, rehearsal/feedback loops Mix as needed: Most organisations pair supervision for safety/standards, with coaching for near-term goals, and mentoring for longer-term development.-

Reflecting on your own setting, what do you think that the terminology differences described make sense?

-

-

All the information in this section of the course comes from the paper Ten simple rules for establishing a mentorship programme by Treasure et al which is an excellent guide to follow. Below the figure we list the ten rules with some of the information in the paper. But please read the whole paper - you can access it through the link, but we also recommend that you download the pdf file underneath.

Rule 1: Define the programme vision and scope'A clear vision and well-defined scope form the foundation upon which the rest of the mentorship programme is built and influences all other rules...The most essential component in this process is the identification of the need that is being addressed...A programme’s vision and scope informs all aspects of a programme’s design, including deciding on the target audience and subject areas of focus.'Rule 2: Develop the organisational structure once the desired outcomes have been defined

'The organisational structure of the mentorship programme is built upon the programme’s scope and outcomes...The programme’s success relies on the organisational roles being founded upon a culture of accountability and openness.'

Rule 3: Plan activities to support programme goals

'Programme support processes should be designed to enable interactions between mentors and mentees, provide equitable access to resources and aid in monitoring progress. Embedding accessibility in these processes is important to ensure benefits for everyone irrespective of differing contexts...Activities work well if the expectations that surround them are discussed at the outset. The selection and sequence of activities will depend on the target audience and the contribution of the activities towards desired outcomes. These activities could either be structured or unstructured...The CORE Africa Research Mentorship Scheme (CARMS) programme is flexible and mentors use a “what works best” approach to support mentee development. Activities range from verbal advice during one-to-one meetings or phone calls, to online and in person lectures and presentations, as well as help with documents, and supplementary learning materials being provided to mentees.'

Rule 4: Recruit mentees with success in mind

'The mentee recruitment and selection processes require careful consideration to attract and select appropriate and committed mentees...Establishing a set of entry requirements is necessary to assess a mentee’s suitability according to the programme goals...Digital privacy of all participants must be ensured and compliance with data protection laws is crucial.'

Rule 5: Develop a mentor support strategy that goes beyond simple recruitment

'When establishing a mentorship programme, it may be tempting to select mentors based solely on their experience or competency in their area of expertise. It is, however, equally important to consider mentors’ interpersonal skills, sensitivity to different mentees’ contexts and their capacity to support a mentee to be successful in the programme. In addition, mentor interest and motivation are important predictors of effective mentoring [2], and mentor commitment and programme understanding are crucial to a programme’s success...Onboarding can help to align mentors to the programme’s mission, vision, and expectations and can provide understanding of the specific needs of the mentees.support should include mindfulness of the time commitment and investment on the part of the mentors: A culture of flexibility and understanding can aid in long-term commitment and avoid mentor burnout.'

Rule 6: Develop and evaluate mentor–mentee matching strategies as an ongoing process

'Careful consideration of the initial mentor–mentee match and continuous monitoring of the match dynamics and productivity are essential to ensure effective mentor–mentee interactions.'

Rule 7: Consider the role that technology will play

'The technologies chosen will play a significant role in how participants can and will engage in the mentorship programme. Technical aspects such as access to the internet or digital infrastructure can also impact participants’ overall experience.'

Rule 8: Ensure communication processes are in place

'In any mentorship programme, communication is a crucial aspect...Although an effective strategy and pathways for communication can offer a platform to connect, experience gained through such connections can have a transformational impact beyond the programme. These communities provide opportunities for discussions and knowledge exchange within a supportive network even after the programme is over.'

Rule 9: Design a M&E plan [Monitoring and Evaluation]

'Ongoing M&E of a programme are crucial for quality improvement and for ensuring an effective mentorship programme...Decide in advance how the mentorship programme will be evaluated and how the impact of the programme will be demonstrated.'

Rule 10: Think about funding and long-term sustainability

'Some mentorship programmes may start with large-scale funding for development, whereas others start small and scale up. For the latter, starting a programme with absolutely no funding or on a shoestring budget using free resources and volunteer labour is feasible. However, financial requirements are likely to arise sooner or later in the programme as it scales.'

-

Reflect on which of the 10 steps described above are likely to be easy and which difficult if a mentoring programme were to be established in your setting.