Distributing learning and knowledge creation to reduce inequity

Section outline

-

A free online course to help build capacity for distributing knowledge to reduce inequity

Note: if you want to gain a certificate for completing this course, you will have to create an account and log in as a student.

The theory:

Inequity is everywhere in higher education between countries, between regions and social and economic groups within countries. There are large variations in access to higher education across the global, regional, socio-economic and cultural divides.

Distributed education is the provision of education where it is needed – taking it to the student rather than the student coming to it - thus overcoming limitations of time and place.

It depends on the use of the internet and online learning. It offers increased equity of access to education for those who cannot physically attend a central campus - due to socio-economic, disability or geographic factors - as well as a reduced carbon footprint.

Networked education depends on contributions from multiple educational institutions. It fosters “collaborative, co-operative and collective inquiry, knowledge-creation and action”. It depends on “trusting relationships… and appropriate communication technologies”.

To gain the benefits of distributing education, knowledge has to be created. Distributing knowledge creation can counter the under-representation of diverse populations in research.

The practice:

Having covered the theory, the course provides aids for the design of courses using a distributed and networked approach. The course concludes with a series of questions to help you assess whether distributed education and knowledge creation are feasible in your setting.

More about the course

Course content

Section 1: Introducing the course - why it matters

Section 2: The concepts of distributed and networked education

Section 3: Digital technologies for education

Section 4: Distributing knowledge creation

Section 5: Open access to educational resources and research

Section 6: Designing programmes which incorporate distributed and networked education

Section 7: Practical aspects of implementing the distribution of education and knowledge creationLearning outcomes of the course

Graduates of the program should be able to:

1. Assess the potential application of the concepts of distributed and networked learning and appropriate digital technologies to proposed education in their setting.

2. Choose appropriate digital tools and platforms for distributed and networked learning and select open access and open educational resources (OERs) to apply in their setting.

4. Engage in distributed knowledge creation (that is, drawing on a network of experts from different settings, for example, in designing both research projects and educational offering).

5. Collaborate in designing programmes which incorporate distributed and networked education and research.

Who is this course for?

Initially the course might be suitable for individuals with responsibility (academic and administrative) for developing education programs in universities, with access to the infrastructure (especially IT) that would enable a distributed approach. You are encouraged to use and adapt the course to suit your own audience and any academic requirements.

Who developed this course?

The course has been developed by an informal group of academics including (in alphabetical order): Johanna Amos, Queen’s University, Canada; Alena Buis, Kwantlen Polytechnic University, Surrey, Canada; Julia Critchley, St. George's, University of London; Anja Harrison, King's College London; Katherine Herbert, Charles Sturt University, Australia; Richard Heller, University of Newcastle, Australia; Stephen Leeder, University of Sydney; Upasana Gitanjali Singh University of KwaZulu Natal, Durban, South Africa; Daniel Otto, Professor for e-learning and digital teaching at the European University for Innovation and Perspective.

The course has been influenced by the open access book: 'The Distributed University for Sustainable Higher Education', and the journal article 'Distributing knowledge creation to include under-represented populations' in The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning.

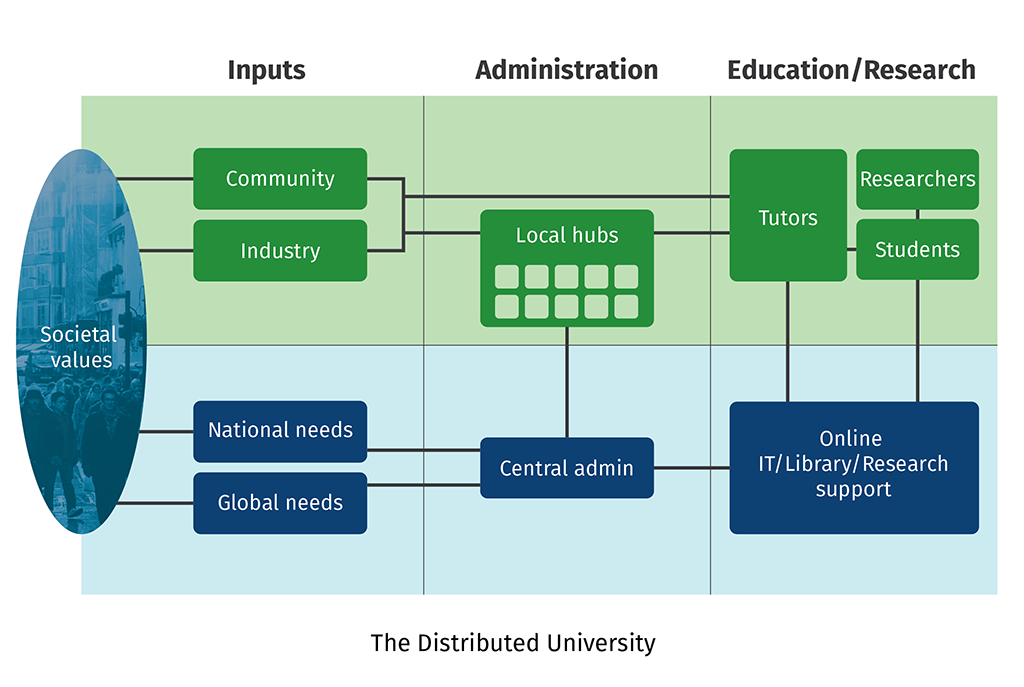

Brief summary of the idea behind the Distributed university, leading to this course

The use of a distributed model of education has the potential to address many of the problems facing higher education today. Large campuses are replaced by local hubs which can be physical or virtual. Education would be largely online and utilises open educational resources, research involves under-represented populations, and publication focuses on 'Diamond Open Access journals' which are community-driven, academic-led, and academic-owned. The carbon footprint of higher education would be drastically reduced, leadership distributed (hence managerialism reduced) and academic autonomy increased. Collaborative development and sharing of open educational resources reduces the drive to the commodification of education, and open publishing reduces the power of commercial publishers. These various initiatives will increase knowledge equity. The distributed model is consistent with societal moves towards decentralisation of the internet (Web 3.0 and 4.0) and federated IT infrastructures (such as the Fediverse for open social media). Decentralised Autonomous Organisations (DAOs) may offer support. The adoption of such a model would encourage new locally driven academic environments and research initiatives responsive to societal needs.

Navigating the course

Please read through each section where you will be able to access resources through embedded hyperlinks. Please post your reflections in the reflections forum in each section (your posts will be visible to those who access the course after you, but the discussion is not active although you are able to change the setting to receive posts from others). You can gain a certificate an automated certificate of completion for the course if you post to each of the reflection forums - see the section at the end.

-

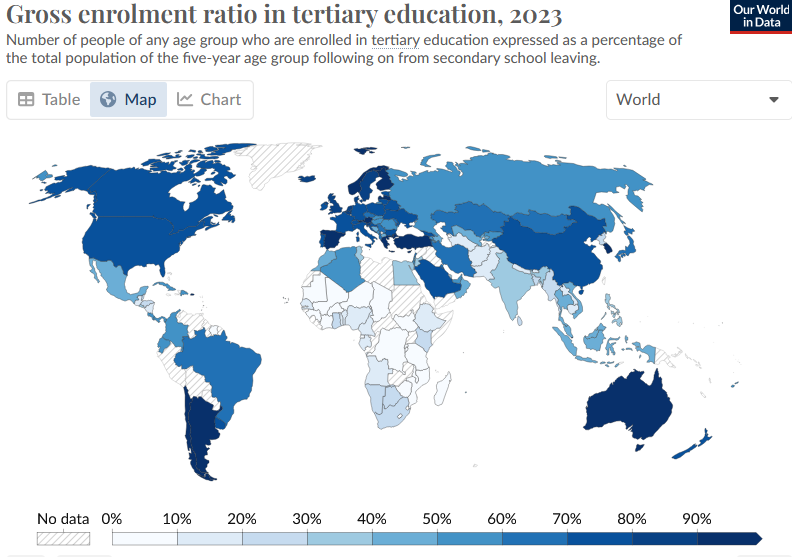

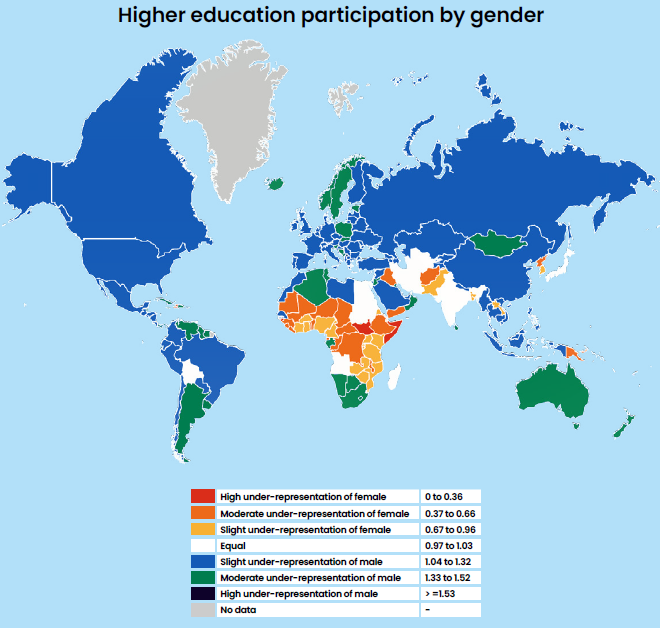

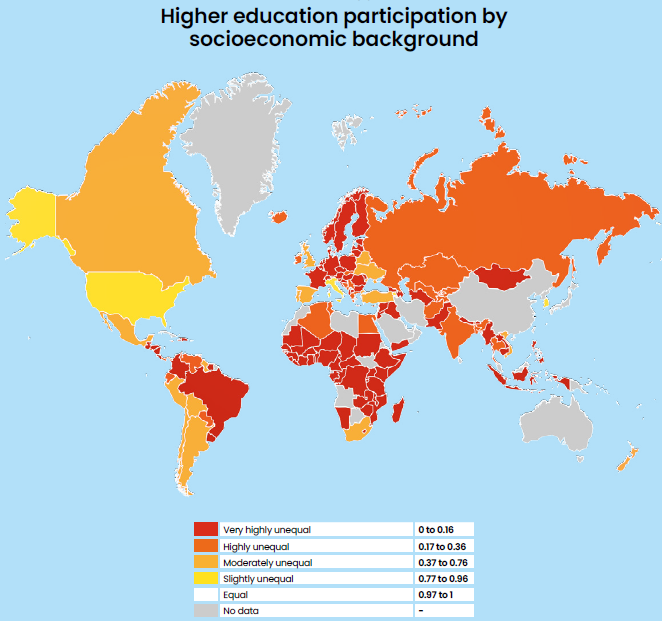

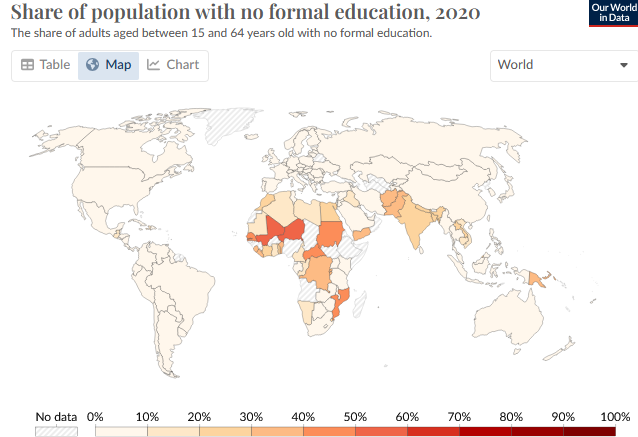

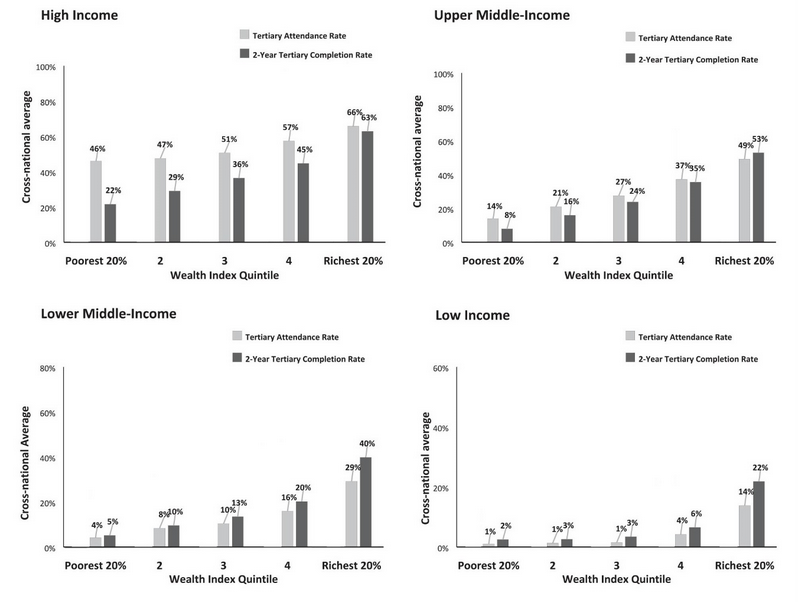

Inequity is everywhere in higher education, between countries, between regions and social and economic groups within countries. These graphs demonstrate some of the issues.

Starting with a world view:

Share of the population enrolled in tertiary education, 2023. From Global Education.

Here are two maps from the World Access to Higher Education Network showing the inequality in access by gender and socioeconomic status Drawing the Global Access Map 2: Understanding higher education inequality across the world

Although the main focus of this course relates to university level knowledge, of course access to tertiary education depends on having completed secondary education, and this graph, also from Global Education reminds us that there is global variation in getting any education at all

Now income disparities between and within global regions:

Disparities according to wealth, within and between global regions. From Buckner & Abdelaziz 2023

Now the urban/rural divide within countries:

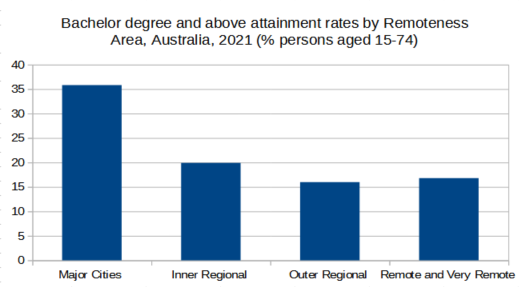

We see social, economic and regional differences within most countries. Here are some data on the urban/rural divide from Australia:

From: Parliament of Australia: Regional and remote higher education: a quick guide

You might like to explore other data that describe and explore regional variations in access to higher education where rates are invariably higher in cities than in regional and remote areas - from the UK, Australia, France, Norway, China, and Africa.

It has been reported that in Australia, somewhere between 8% and 10% of Indigenous people have a university degree, compared with 32% of the broader Australia population.

The reasons for each of these inequities are complex, and cannot be dissociated from access to primary and secondary education. However, our focus here is on tertiary, university education.

We will be covering the theory of how distributing both the learning and the creation of knowledge can help reduce knowledge inequity, and also want to provide practical skills for those who access the course. We hope that you will become practitioners of, and advocates for, this approach to higher education.-

Please reflect on the relevance of examples given here on inequity in access to higher education and add any examples you can offer.

-

-

Learning objectives

By the end of this section of the course, you should be able to:

-

Describe the principles and theories underlying distributed and networked education.

-

Explain the potential of distributed and networked education to enhance access to higher education.

-

Reflect on case studies which describe distributed and networked education programmes.

By distributed education we mean the provision of education where it is needed – taking it to the student rather than the student coming to it - thus overcoming limitations of time and place. A useful definition states that distributed education occurs “when the teacher and student are situated in separate locations and learning occurs through the use of technologies (such as video and internet), which may be part of a wholly distance education programme or supplementary to traditional instruction." Hybrid education, combining online and face-to-face, has become common after the experience of the Covid pandemic, but usually implies that courses are designed and delivered centrally are partially distributed online.

Structural change can offer a more thorough distribution where students remain in their populations while they access online education. Online delivery can be supplemented through local hubs where face-to-face options are required - as shown in this diagram taken from The Distributed University for Sustainable Higher Education. The local hubs may be physical or virtual and can include international settings.

Information derived from distributed populations and incorporated into educational programmes to make them more relevant to students from those populations, and can be used to create knowledge through research including local populations. The notion of distributing knowledge creation is discussed further in a later section of the course.

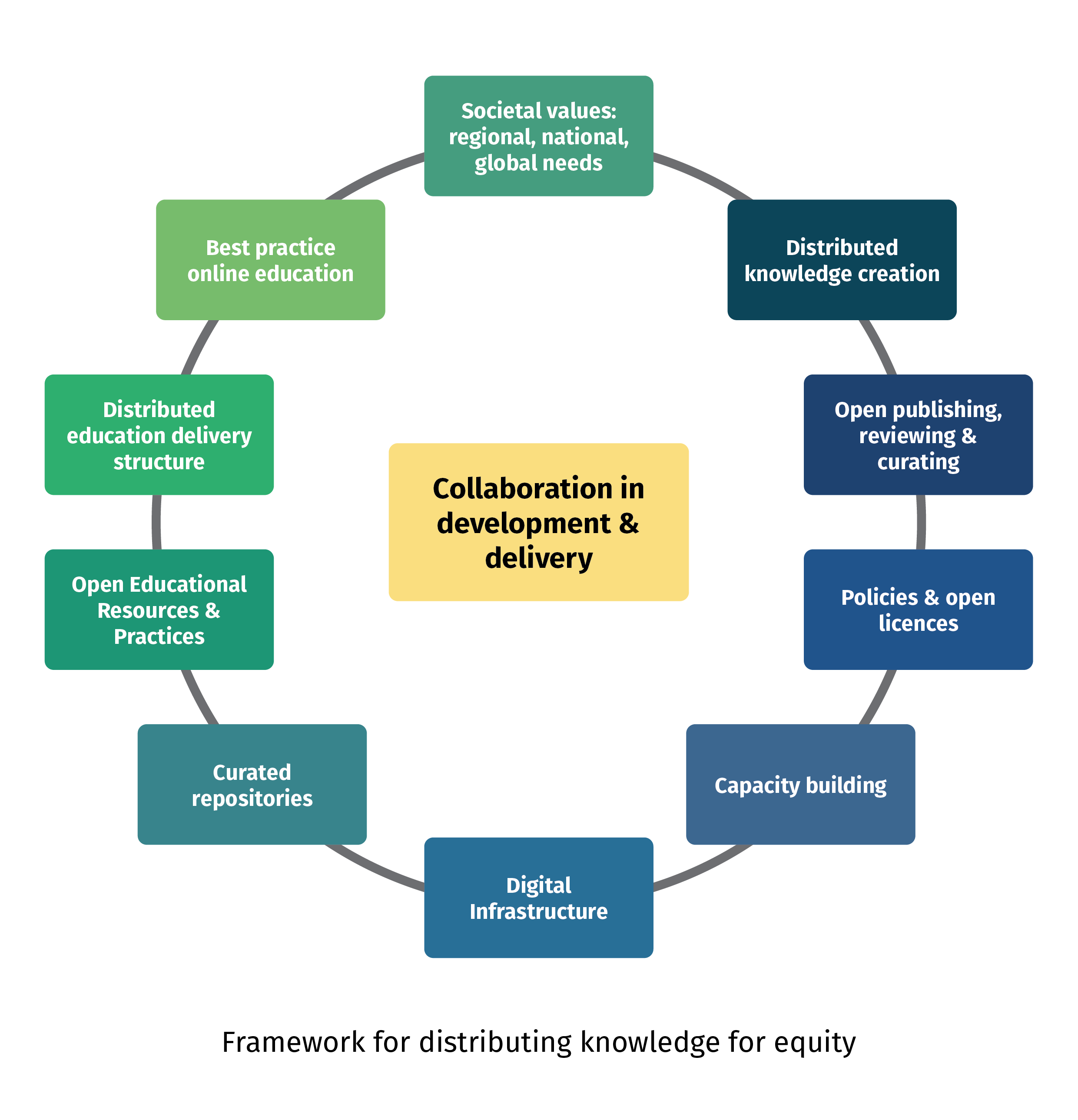

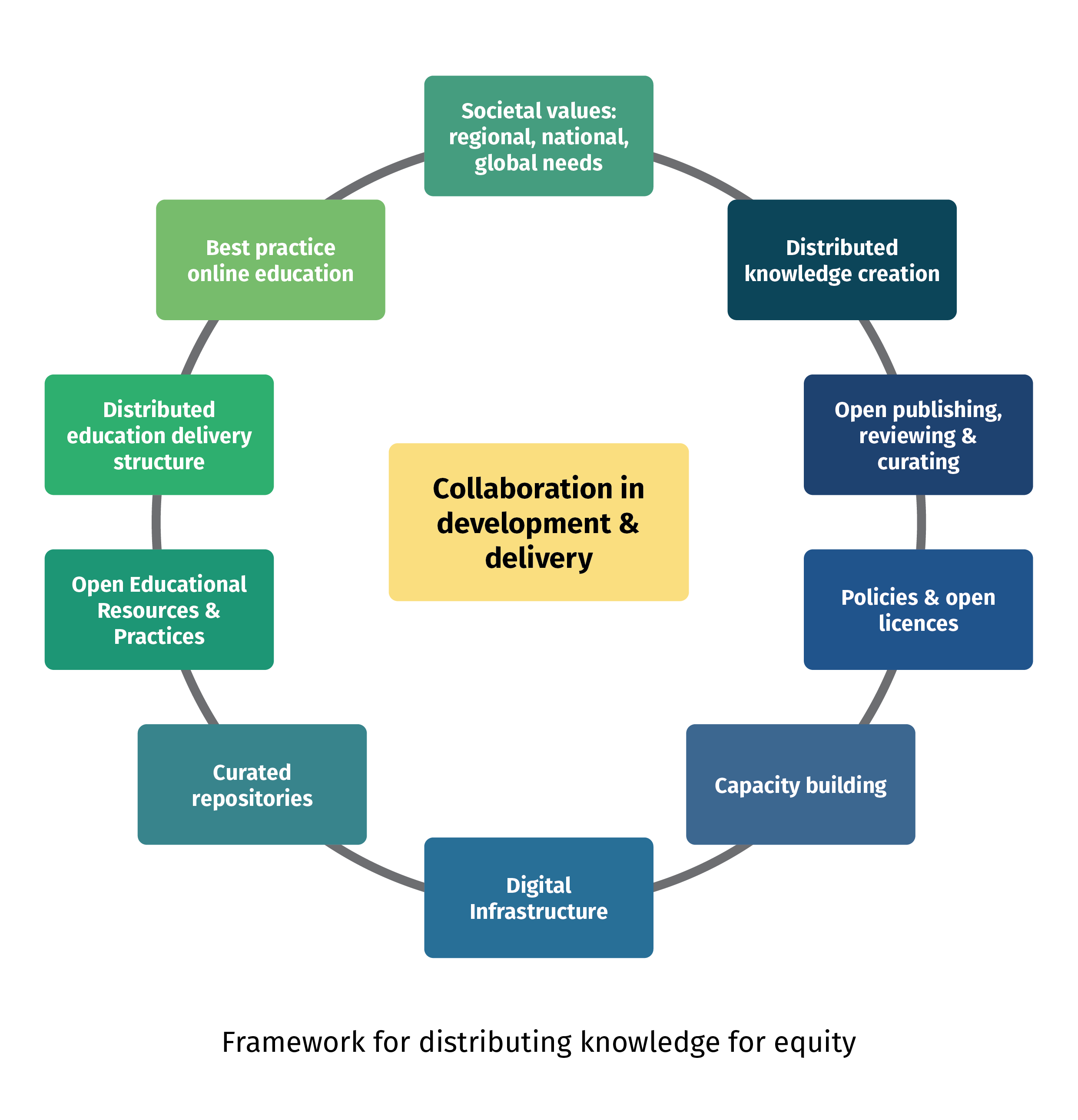

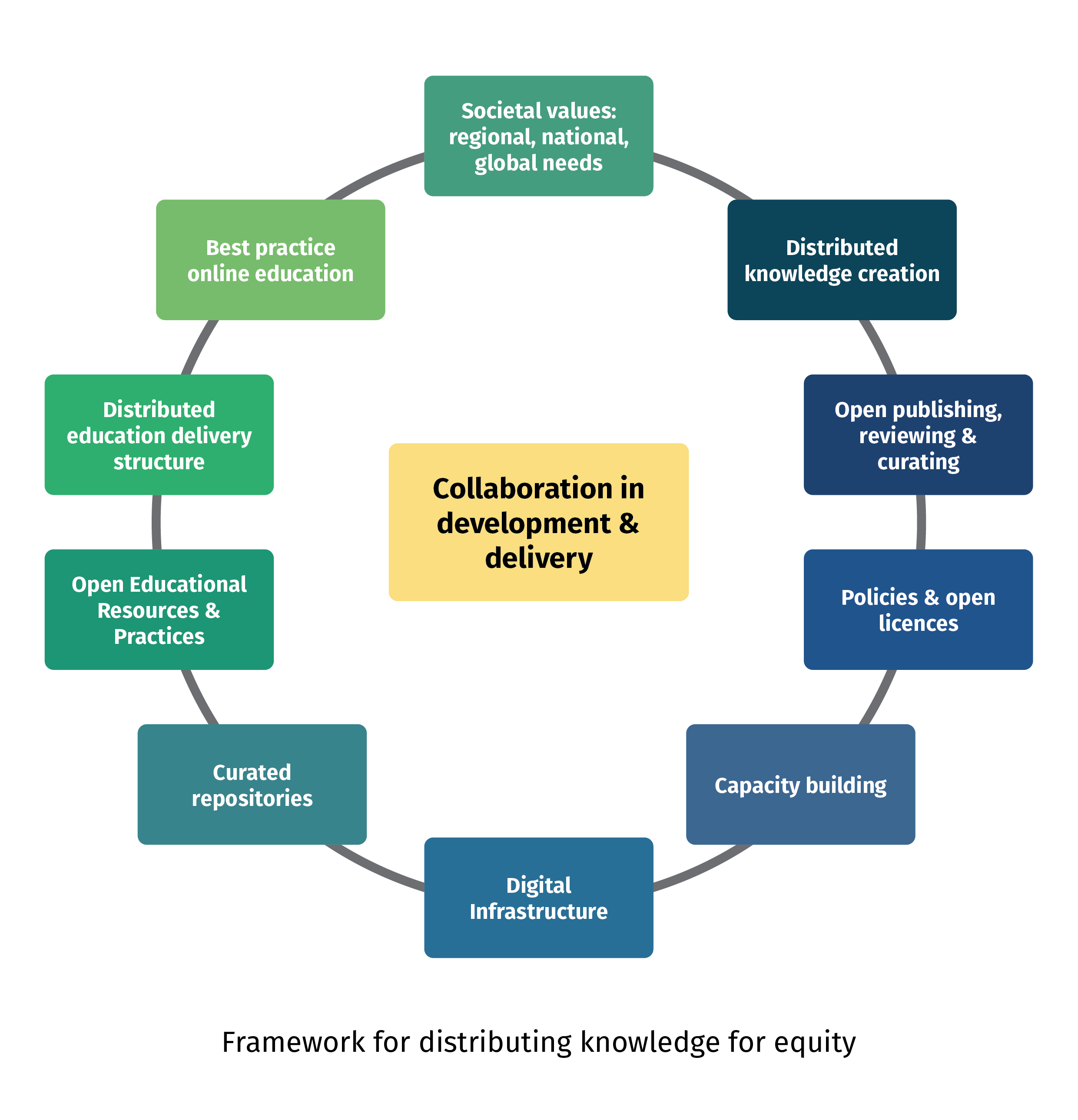

Distributing knowledge and its creation should be considered within a framework for increasing knowledge for equity. The diagram below (which first appeared in Distributing knowledge creation to include under-represented populations in The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning (in press)) attempts to show the various components of this framework We will be discussing each aspect at various points in this course.

There are many potential advantages of a distributed model. These include increased equity of access to education for those who cannot physically attend a central campus - due to socio-economic, disability or geographic factors. International education becomes more feasible than moving country. The impact on the climate can be markedly reduced by online rather than face-to-face education. Thanks to modern information technology, he way we access and process information today has moved on from passive learning - such as through lectures - to active learning through the internet.

By networked education we mean education that depends on contributions from different institutions. It has been formally defined as learning that fosters “collaborative, co-operative and collective inquiry, knowledge-creation and action”. It depends on “trusting relationships… and appropriate communication technologies”. Modern digital communications technology allows for connectivity that underpins the ability to create networks. The goal for networked learning, beside offering education that has benefited by collaborative development, is to promote "connections: between people, between sites of learning and action, between ideas, resources and solutions" that may pay dividends in the future practice of the students who have had the benefit of networked learning. Definitions and terminology are difficult, and we do not want to spend too much time on terminology. Here we are thinking of networks between the providers of education, although networks can be developed between learners themselves. [Note: distributed learning is a term used in artificial intelligence (AI) for the process of training machine learning models within a network. We will be touching on the importance of AI in distributed education later in the course, but not in this sense.]

A distributed and networked approach combines the benefits of both. Best practices and infrastructure can be developed and shared, higher proportions of populations at need of increased access can be reached, and research opportunities enhanced. Universities who collaborate in such a network would gain by being able to meet the mission of reaching at need populations, of having access to infrastructure and research opportunities and being able to incorporate course developments into their own programmes.

You might like to explore some of these case studies

Distributed education. Australia was a pioneer in distance education due to the large size of the country and dispersed population. We have already pointed to the regional university study hubs. Researchers from Queensland, Australia describe experience in a multi campus university in New Generation Distributed Learning: Models of connecting students across distance and cultural boundaries. A group from an open university in Pakistan report on their experience. From outside the traditional higher education sector, Peoples-uni was a fully online postgraduate distributed programme with tutors from 50 countries and students from 100 countries.

Networked education. The Biostatistics Collaboration of Australia comprises a number of universities offering a national programme of postgraudate biostatistics courses. The OERu is a network of recognised universities, polytechnics and community colleges from five continents offering online education based on Open Educational Resources. CanadARThistory is a collaboration between five educational institutions in Canada to offer open access to a course which reimagines the history of Canadian art.

An example of inequity in international education. A study, using 2022 data for higher education enrolment of international students in Australian universities, found three South-East Asian countries with very high access rates These are Singapore (403 students in Australia per 100,000 population), Brunei Daraussalam (115 per 100,000) and Malaysia (63 per 100,000). At the same time, Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, the Philippines, and Indonesia had rates less than 5 per 100,000 population.

Malaysia and Singapore together provided 47% of South-East Asian international student numbers in Australia in 2022 but comprised only 6% of the total population of South-East Asia. Indonesia provided 12% of South-East Asian international student numbers in Australia but comprised 40% of South-East Asia’s combined population.

Looking more broadly, in 2022, per 100,000 population, median rates of students coming to Australian universities were: Indian subcontinent 42, Pacific 28.9, China 10.5, South-East Asia 5.8, Sub-Saharan Africa 0.5: there was wide variation between countries within these regions.

These differences do not reflect the needs for higher education. In common with other countries, Australia’s international education is driven by the fees that students pay which are used by universities to cross-subsidise education and research.

An alternative approach would be to adopt a strategy for international education that reflects global needs - captured by the term knowledge diplomacy refers to ‘a new approach to understanding the role of international higher education, research, and innovation in strengthening relations among countries and addressing common global challenges.’ It depends on ‘collaboration, reciprocity, and mutuality.’

Distributing education online has great potential to counter inequities in access as these case studies illustrate.

-

Please reflect on what you have read about distributed and networked learning and post here how you would define these concepts and how they might be applicable in your setting.

-

-

By the end of this section on digital technologies for education, you should be able to:

Demonstrate an understanding of the evolving role of digital technologies, especially online learning, in higher education and its relevance to distributing education widely

Assess proficiency in using digital technologies for education to address potential barriers to implementing these technologies in different educational settings.

Identify appropriate digital tools and platforms that facilitate distributed and networked learning.

Place the distributed model in the context of societal moves towards decentralisation of the web and federated digital infrastructure.

Background

There is a digital transformation throughout society, and education is no different. If you are accessing this course on distributing learning, you are taking part in this transformation. The advent of the internet allowed distance learning, already used to bring education to those unable to travel to a point of delivery, to evolve into online learning. A perceptive paper in 1996, The evolution of distance education: Emerging technologies and distributed learning, speculated how emerging technologies might reshape both face to face and distance education.

The digital transformation of higher education, accelerated by the Covid pandemic, is well under way. As Singh et al state in Digital Teaching, Learning and Assessment The Way Forward,

‘Digital teaching and learning has shifted from just an option...to a development where education revolves around the delivery primarily on a digital platform.’

In From the margins to the mainstream: The online learning rethink and its implications for enhancing student equity Stone focuses on equity ‘From being largely at the margins of higher education for many years, online learning now finds itself in the mainstream...Evidence tells us that online learning plays a significant role in enhancing student equity, widening higher education access and participation for many students who would have found it difficult, if not impossible, to attend university on campus’.

While the advent of online teaching can be seen as a threat to traditional university teaching, it offers wonderful opportunities for the key notions of distributing education widely as we present in this course. However, as we discuss below, there are dangers in the uncritical adoption of technology in education.

There are multiple digital technologies in use and under development for educational purposes. These include various learning management systems where the educational resources are posted and discussions assessments and assignments hosted. Tools for communication including social media are critical, and gaming, simulations and virtual reality experiences are becoming common. Artificial Intelligence (AI) options are both a threat and an opportunity, as we will discuss in more detail below.

As well as allowing for the wide distribution of learning, there are many educational advantages of online education. The graphic below, from Haleem et al, shows some of the features of the digital classroom

Technology in education goes beyond the classroom. As a UNESCO report states: ‘Digital platforms are not simply tools at the service of teachers and students; they play a far more pivotal role in educational governance.’ We will return to this report in the section on open access. A similar concept is articulated ‘digital learning can be seen as part of the ecosystem of modern higher education’ as higher education institutions themselves undergo digital transformation.

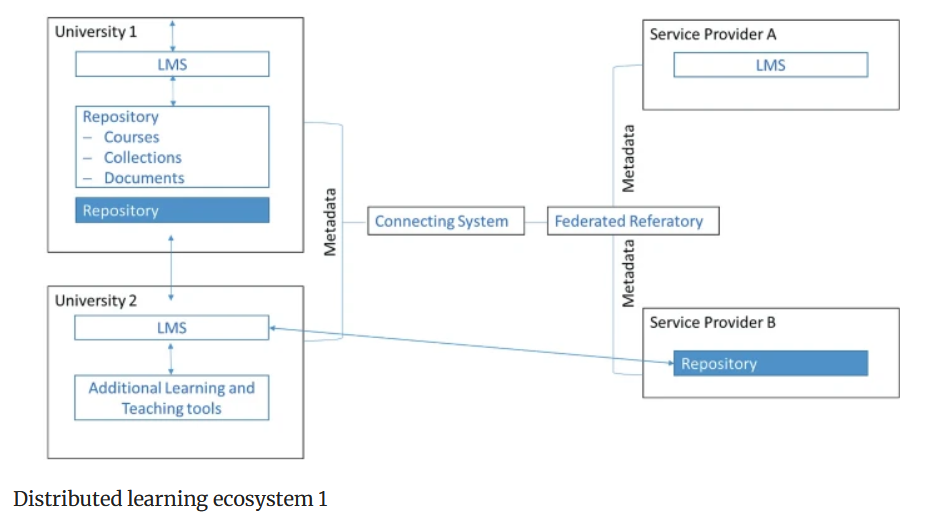

In an introductory chapter to the book Distributed Learning Ecosystems in Education, Otto and Kerres have described the concept of distributed learning ecosystems as an integrated approach that enables learners to access and use learning content and share resources.This builds on the internet being the emerging space where learning takes place. The figure from their chapter shows the potential for individual open repositories to exchange with each other, to contribute to a distributed learning ecosystem.

The distributed learning ecosystem, from Otto and Kerres

There are many other benefits, such as for the environment - online education has a much lower carbon footprint than face-to-face teaching. A paper Digital Learning and Sustainable Development suggests: ‘Digital learning...saves resources and CO2 emissions, thus contributing to the protection of the climate...it democratizes the educational sector by making learning resources more easily accessible to learners all over the world; it helps to connect people from different cultures by allowing for intercultural exchange among students without additional travelling; fourth, it facilitates a self-regulated learner-centered style of learning that is well-suited to empower learners to become agents of a sustainable development.’

Educational technology.

Educational technology (or edutech or edtech) is defined as ‘the combined use of computer hardware, softwares and educational theory and practice to facilitate learning. When referred to with its abbreviation, "EdTech", it often refers to the industry of companies that create educational technology.’ These companies are privately owned and create profits not only from the sale of their products, but from the sale of the data derived from the students and their educational journey. The potential for the commodification of education in this way is confirmed by McKinsey ‘US venture funding for education technology (edtech) grew from $1 billion to $8 billion between 2017 and 2021’. The same post offers advice to readers: ‘Growing competition in online education suggests providers may need to take bold action. Five strategic moves could help them compete and grow while meeting the needs of learners.’

The dangers of relying on the EdTech industry are illustrated nicely: ‘Universities in the Global North are embracing digital platforms as the basis for the delivery of content, assessment of proficiencies and cost reduction. Those platforms are surveillance machines, a manifestation of surveillance capitalism. They abstract students and academics alike, embodying a politics in which people are addressed as digital artefacts – instances of when, what and how they have interacted online rather than being respected as people who are more than a data point on an educational social graph.’

Luckily, there are many other players in this area, such as OpenEdTech who want to bring trust to educational technology ‘Too much of the software being marketed for education is designed by startups and Big Tech whose main purpose is to maximise profits for investors, which leads to proprietary subscription platforms designed around trapping your data and centralised products that ignore local cultural differences. When investors become unhappy these products can simply disappear. These are not ideal for designing our education system’.

The ‘datafication’ of universities themselves has also been noted: ‘Universities recognise the potential value of their digital data and strive to become data-driven organisations that collect, analyse, structure, manage, and use data and data products in their strategic and operational activities.’ These functions may be conducted internally or outsourced to EdTech companies. In either case, this might be part of the commercialisation of higher education that takes the sector away from its intended function of meeting the educational needs of society towards a neoliberal agenda.

The role of AI (artificial intelligence)

There appear to be three main areas in which AI is used in online learning, according to a systematic review of reported studies: ‘(1) how AI technologies are used in online teaching and learning processes, (2) how algorithms are used for the recognition, identification, and prediction of students’ behaviors, and (3) adaptive and personalized learning empowered through artificial intelligence technologies.’ The authors conclude ‘developing policies and strategies is a high priority for educational institutions to better benefit from artificial intelligence technologies and design human-centered online learning processes.’

More detail is given in the editorial to introduce a Special Issue of the International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning: Artificial Intelligence in Open and Distributed Learning: Does It Facilitate or Hinder Teaching and Learning? ‘Artificial intelligence (AI) is a rapidly evolving field with the potential to revolutionize various aspects of education, especially in open and distributed learning, including distance education, hybrid learning, and blended learning. AI can transform curriculum design, content delivery, assessment, feedback, learner support, and learning analytics (Chen et al., 2020). AI offers personalized and adaptive learning paths based on learners' preferences, needs, goals, and performance, enhancing their educational experience (Holmes et al., 2023). It also provides timely feedback and guidance, fostering engagement and motivation. AI creates interactive and immersive learning environments, such as games, simulations, and virtual reality, sparking learners' interest and involvement. It promotes social and collaborative learning by facilitating communication and cooperation among learners, instructors, and resources (Holmes et al., 2023).’

David Wiley has an excellent YouTube presentation

His primary argument is that 'generative AI is, or soon will be, a more effective tool for increasing access to educational opportunities than OER' (Open Educational Resources). This is a long presentation, but you can navigate to the parts that interest you!An article in the Conversation sounds a warning: ‘Every few years, an emerging technology shows up at the doorstep of schools and universities promising to transform education. The most recent? Technologies and apps that include or are powered by generative artificial intelligence, also known as GenAI. As optimistic as these visions of the future may be, the realities of educational technology over the past few decades have not lived up to their promises.’

In ‘On the Limits of AI in Education’, Selwyn has issued ‘a call for slowing down and recalibrating current discussions around AI and education – paying more attention to issues of power, resistance and the possibility of re-imagining education AI along more equitable and educationally beneficial lines.’

It seems likely that explorations of the role of AI in distributing education will expand rather than slow down, and that there is considerable scope for a major contribution, even revolution. In any case, there will be a need to update what we have written here as this evolving field develops and grows over time.

Technology in context

Another article in the Conversation includes these quotes: ‘Policymakers and educators should consider technology as one part of a toolkit of responses for making informed decisions about what technologies align with more equitable and just education futures...the future of education is about healthy social connection and social justice.’

Federated infrastructures and the decentralised web

The need for an understanding of the benefits, as well as the concerns about the move towards online learning is illustrated by these comments from a Canadian Digital Learning Research Association survey which found: ' (a) online and hybrid learning presents challenges of access for students marginalized by “race,” class, and location; (b) online and hybrid learning supports equity, diversity, and inclusion by increasing access and flexibility; (c) pedagogy and course design are central to ensuring that online and/or hybrid learning supports equity, diversity, and inclusion; and (d) student experiences and expectations around online learning indicate a need for support and flexibility.'

The distributed model, which underpins the transformations outlined in this book, is consistent with societal moves towards decentralisation of the internet. Decentralisation, giving greater control and ownership to users themselves, is a key component of the development of the internet towards web 3.0. Decentralisation leads to Federated IT infrastructures—a nice description comes from the commercial sector but I include it here as it makes the notion quite clear: 'A fully federated architecture creates a network of independent systems that can still work together. Each system, like a company department, controls its own data and functions, but they can all share information securely following agreed-upon rules. This allows for collaboration without relinquishing control, making it useful for complex organizations with separate needs.'

As a reaction to the domination and manipulation of the social media giants, the Fediverse has been developed to decentralise social networks. Each local server sets it own rules and allows for information to flow between each other. You can access a lovely (short) video Introducing the Fediverse: a New Era of Social Media by Elena Rossini, hosted on the federated PeerTube.

In conclusion

Distributing education to create equitable educational futures depends on technology, and we hope that this section of the course has identified some of this potential, including methods, benefits - and dangers.

-

Please offer your reflection on the potential benefits and dangers of increasing the use of digital technologies in education.

-

-

By the end of this section of the course you should be able to:

Understand the differences and synergies between distributing knowledge dissemination and distributing knowledge creation

Reflect on the advantages of including under-represented individuals, communities and societies in the creation of knowledge

Describe the three main areas for distributing knowledge creation (research, research publications, and educational resources)

Consider some practical ways in which knowledge creation might be distributed to under-represented populations

Introduction

Note: Much of the content of this section is also to be found in the journal article 'Distributing knowledge creation to include under-represented populations' in The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning (in press).

We have already discussed the benefits of distributing education, that is the dissemination of knowledge, but before it is disseminated knowledge has to be created. This part of the course discusses the distribution of knowledge creation.

The reasons can be summarised as:

Research that incorporates the experience of distributed populations and population groups will give voice to to those groups and will have wider general applicability than research comes from limited populations.

Knowledge derived from research should be published and disseminated in ways that make it available to distributed populations to increase the likelihood that the research findings will be incorporated into policy and action across populations.

The incorporation of knowledge gained from distributed population groups into the educational experience will enrich it, and like the knowledge, make it more relevant to the whole population.

Three issues demonstrate the need for distributing knowledge creation

1. Research under-represents diverse populations.

Research on many topics can be enriched by the perspectives that come with the distribution of talent and representation of voices. Current research studies frequently exclude women, certain geographical areas (especially those in the Global South), and marginalised groups. For example, the lack of female and racial representation in the conduct of clinical trials in medicine diminishes the application of the research findings. Research in psychology and human behaviour has been criticised for focusing on western, educated, industrialised, rich, and democratic (WEIRD) societies. Oxford historian Peter Francopan, in his wide-ranging ‘The Earth Transformed: An Untold History’ (Francopan, 2023) writes:

‘Study of the past has been dominated by the attention paid to the ‘global north’...with the history of other regions often relegated to secondary significance or ignored entirely. That same pattern applies to climate science and research into climate history, where there are vast regions, periods and peoples that receive little attention, investment, and investigation...Much of history has been written by people living in cities, for people living in cities, and has focused on the lives of those who lived in cities.’

Hungarian social researcher Márton Demeter writes that

‘...the accumulation of academic capital is radically uneven with very high concentrations in a few core countries...the world of science can be separated for a few “winner” or core and many more “loser” or peripheral countries.’

He also quotes the observation that ‘loser-country scientists were cited less frequently than winner-country scientists, even in cases where they had been published in the very same journal.’

The philosophical concept of standpoint epistemology (or standpoint theory of knowledge) is relevant, and nicely boiled down by Georgetown University philosopher Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò as: 1) Knowledge is socially situated 2) Marginalized people have some positional advantages in gaining some forms of knowledge 3) Research programs ought to reflect these facts. Amy Allen, a liberal arts research professor of philosophy and women's, gender, and sexuality studies at The Pennsylvania State University, states: ‘Feminist standpoint theory has expanded beyond gender to encompass categories such as race and social class. Recent scholarship calls for studying standpoints of Third World groups in Western societies and marginalized groups in international contexts.’

Under-representation of indigenous peoples in research is now widely recognised. An example comes from the Arctic people:

‘Indigenous Peoples' knowledge systems hold methodologies and assessment processes that provide pathways for knowing and understanding the Arctic, which address all aspects of life, including the spiritual, cultural, and ecological, all in interlinked and supporting ways. For too long, Indigenous Peoples of the Arctic and their knowledges have not been equitably included in many research activities.’

In ‘Decolonizing knowledge production. Perspectives from the Global South’ representatives from India, Mexico, Brazil, Ghana and Tunisia discussed:

‘The production of knowledge in the global academic field is still highly unevenly distributed. Western knowledge, which originated in Western Europe and was deepened in the transatlantic exchange with North America, is still considered an often unquestioned reference in many academic disciplines. Thus, this specific, regional form of knowledge production has become universalized.’

In a supplementary issue of the Journal of the British Academy, Repositioning of Africa in knowledge production: shaking off historical stigmas, Crawford and colleagues summarise:

‘Contemporary debates on decolonising knowledge production, inclusive of research on Africa, are crucial and challenge researchers to reflect on the legacies of colonial power relations that continue to permeate the production of knowledge about the continent, its peoples, and societies.’

In trying to further understand the reasons, Maru Mormina and Romina Istratii ask and answer the question:

‘Why do many countries in the Global South remain behind when it comes to knowledge production and use, despite decades-long efforts to strengthen research capacity?

We think this is because the North still looks at the South with a ‘deficit mentality,’ according to which the latter has the problems and the former the solutions. From this standpoint, northern-led capacity development initiatives fail to recognise the South’s rich and diverse knowledge traditions and systems. Instead, they continue to impose monolithic blueprints of knowledge production, therefore re-inscribing colonial patterns of intellectual Western hegemony.”

A prestigious medical journal has followed this theme in The Lancet and colonialism: past, present, and future saying:

‘Institutions for knowledge production and dissemination, including academic journals, were central to supporting colonialism and its contemporary legacies ...Around the turn of the 20th century, The Lancet helped legitimise the field of tropical medicine, which was designed to facilitate exploitation of colonised places and people by colonisers...The Lancet must recognise and engage more with different methodologies of knowledge production, beyond the ways of knowing and the types of knowledge that it currently publishes...The Lancet must divest from the power of its centrality that makes it perpetuate various forms of colonialism.’

A case study - listening to patients An example of distributed knowledge creation is the initial identification of Long Covid which 'has a strong claim to be the first illness created through patients finding one another on Twitter: it moved from patients, through various media, to formal clinical and policy channels in just a few months.' 2. Research publications are biased towards the Global North

This bias is due both to lack of research capacity and biases in the publication system. Even when research is performed in these populations it may not be accessible to those who might apply the results. The relative lack of scientific publications by authors in the Global South has been widely discussed. Political scientists Medie and Kang report fewer than 3% of articles in four gender and politics journals published in the Global North were written by authors from the Global North. A geographical perspective on sub-Saharan Africa finds that digital content is even more unevenly geographically distributed than academic articles.

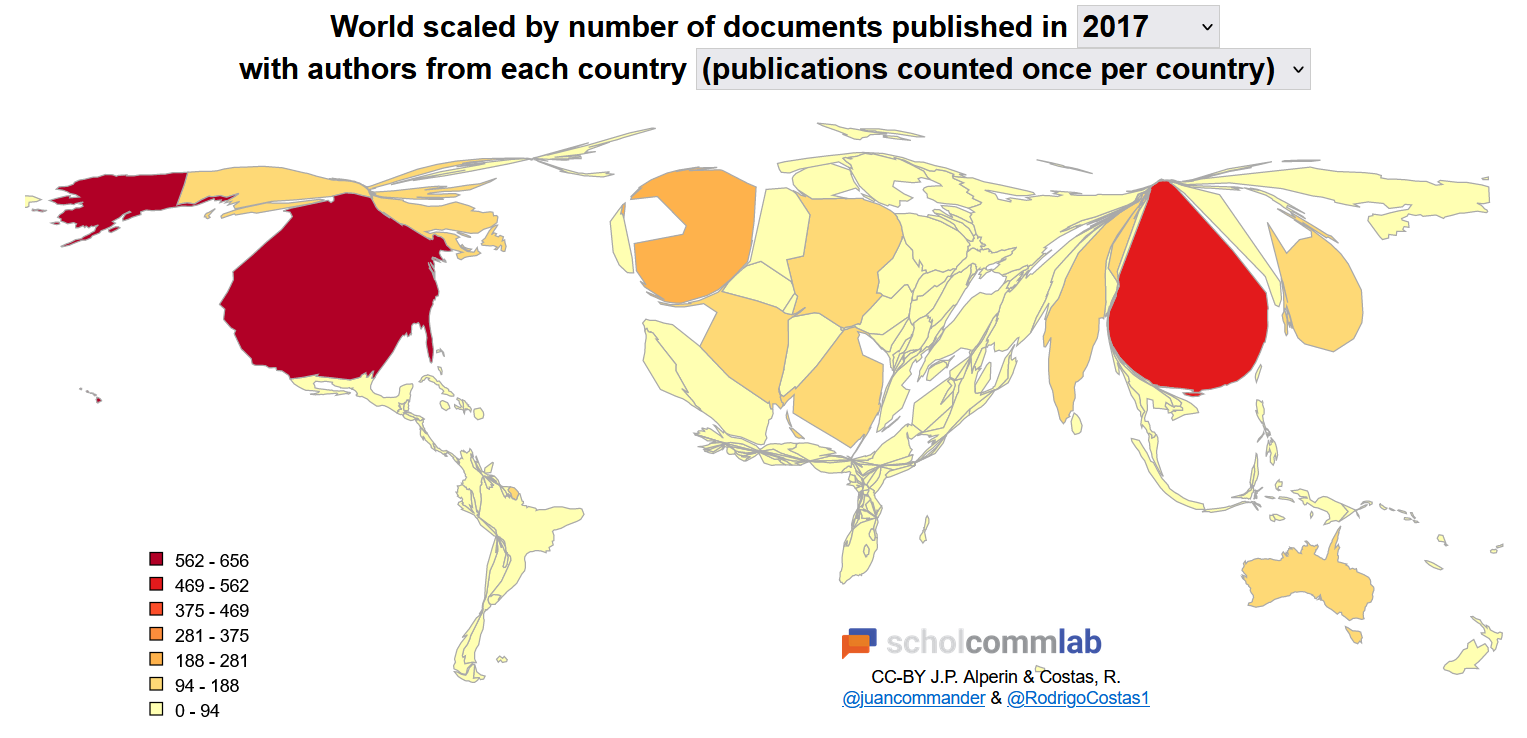

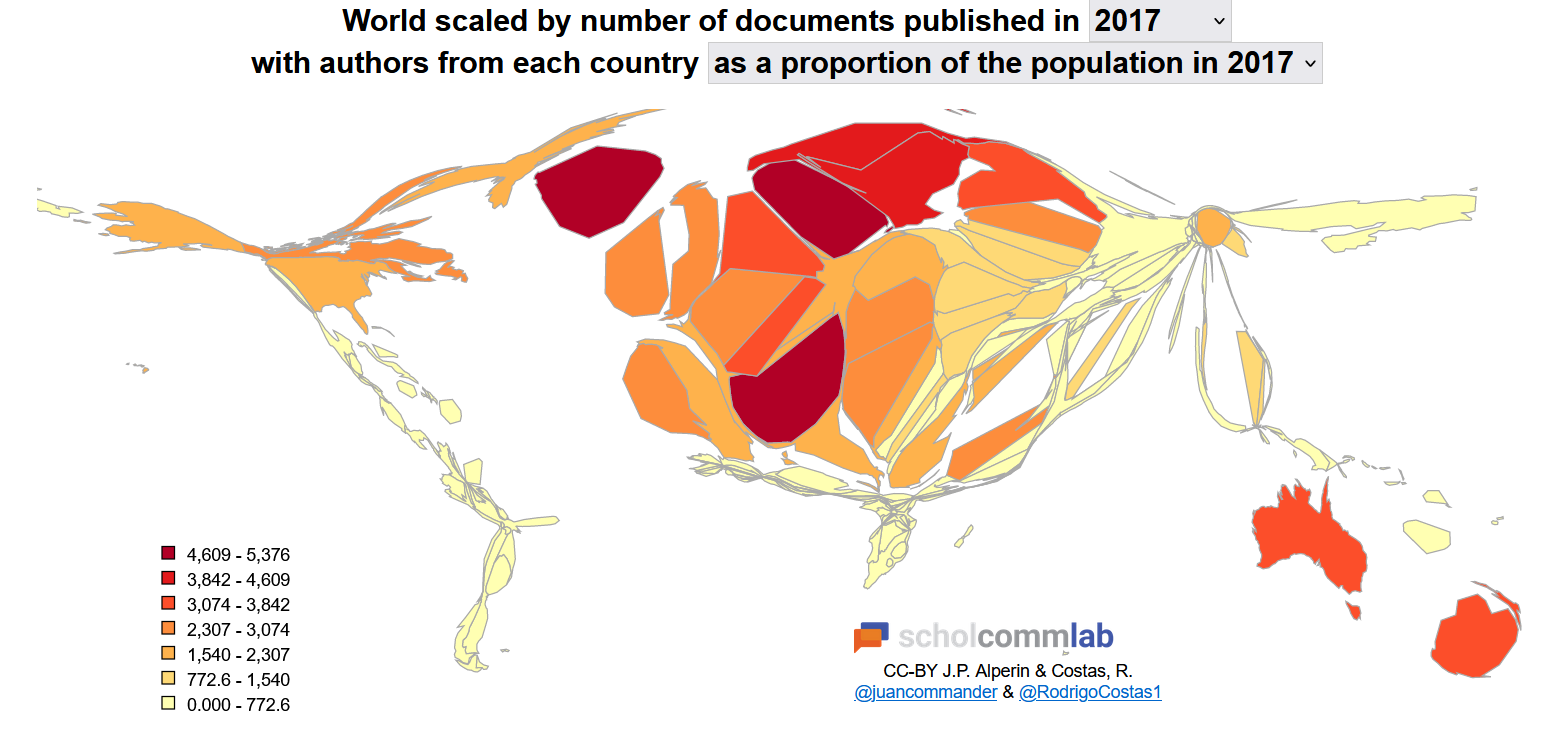

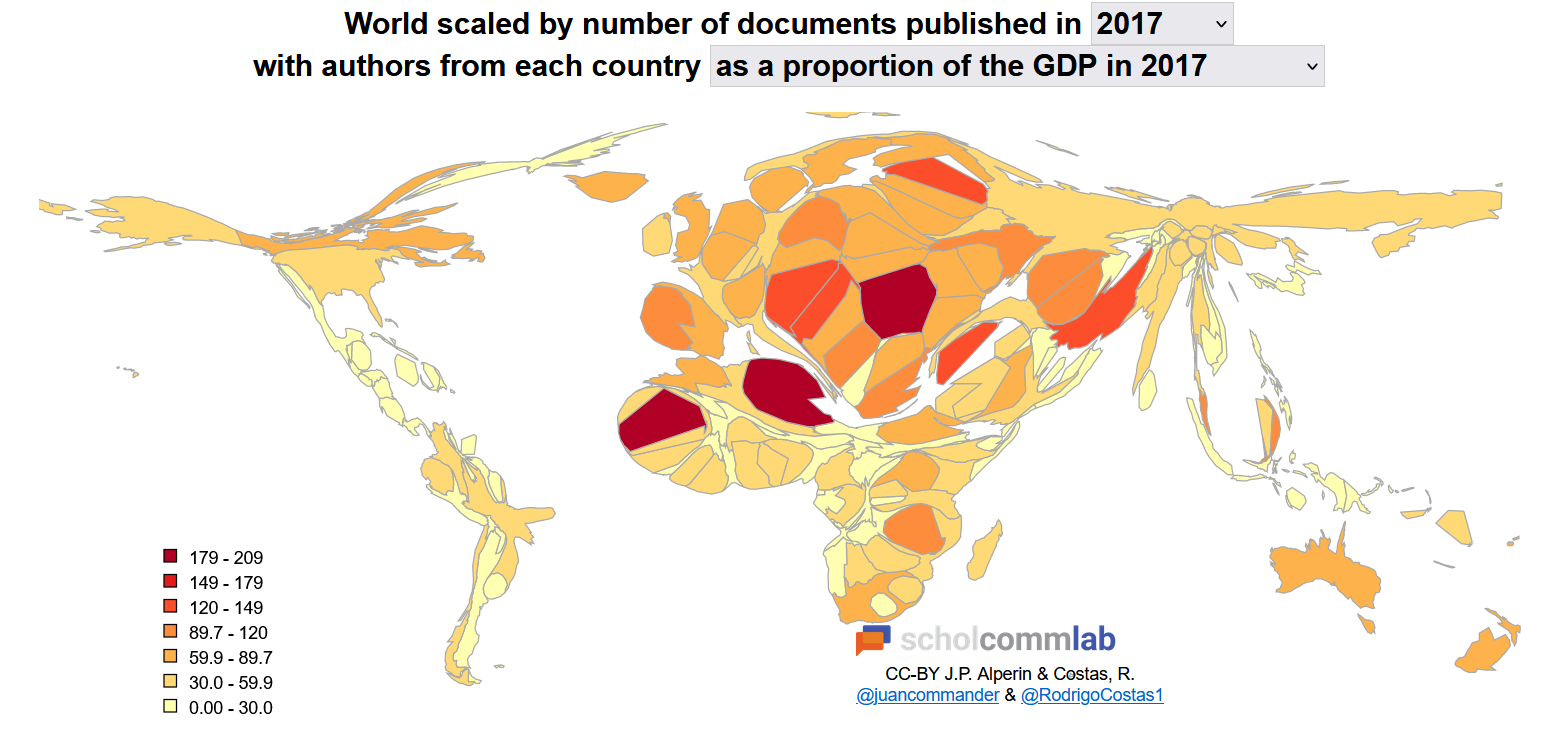

Three graphs scale the apparent size of each country by the number of documents cited in the Web of Science. When raw numbers are examined by country, there are gross global differences (Figure 1). These differences are attenuated when the numbers are adjusted for the population size of each country, (Figure 2). However, it is not until the figures are adjusted for GDP (Figure 3), that African countries at last become visible in the map.

The

patterns may underestimate the geographical disparities as the Web of

Science has

been criticised

for being structurally biased ‘against

research produced in non-Western countries, non-English language

research, and research from the arts, humanities, and social

sciences.’

Research

on health journals

published in 13 African countries found that most journals were not

indexed. Other valuable research may not appear in journals biased

against non-Global North sources. Article processing charges levied

on the authors or their institutions are further barriers to

publication.

The

patterns may underestimate the geographical disparities as the Web of

Science has

been criticised

for being structurally biased ‘against

research produced in non-Western countries, non-English language

research, and research from the arts, humanities, and social

sciences.’

Research

on health journals

published in 13 African countries found that most journals were not

indexed. Other valuable research may not appear in journals biased

against non-Global North sources. Article processing charges levied

on the authors or their institutions are further barriers to

publication. Research funding, and the research agenda that this funding meets, also favours the Global North, and where North-South research collaborations exist they are dominated by collaborators from the Global North. A study of Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTDs), which by their nature are endemic in low-to-middle-income countries, found that between the years 2007 and 2022 organisations in non-endemic countries received 75% of direct research funding on NTDs and 70% of indirect research funding on NTDs. An editorial in the SomaliHealth Action Journal (SHAJ) documents considerable dependence on external institutions and organisations, in particular North-American and European, on authorship, institutional affiliation and funding of published health research of relevance to Somalia. Most of the research of direct relevance to Somalia were authored by non-Somalis only, and did not address current and emerging health priorities for Somalia.

3. Educational resources are biased in the same way.

If population groups and geographical regions are are relatively under-represented in the research literature, educational examples from these populations are unlikely to find their way into the curriculum. This may be compounded by similar under-representation among the academic staff of educational institutions. Postian reviewed the courses at Villanova University and found that of the authors represented in undergraduate introductory courses, 70% were men, 90% worked in or originated from the Global North, and 7% were Black academic authors.

Ghai and colleagues audited recommended reading materials in the undergraduate curriculum for the psychological and behavioural sciences bachelor’s degree.

‘All first authors of primary research papers were affiliated with a university in a high-income country — 60% were from the United States, with 20% from the United Kingdom, 17% from Europe and 3% from Oceania. No author was affiliated with an institution based in Africa, Asia or Latin America. most of the research studies taught to undergraduates were also based on groups that were predominantly (67%) from the global north. Only 12% of articles included research participants from both the global north and the global south; no study in our reading lists focused on a group solely from the global south. Our syllabus lacked diversity even within the studies: less than 20% of articles reported diversity markers such as income or race, and only 3% mentioned participants’ urban or rural location.’

Tamimi and colleagues found their global health and social medicine curriculum biased towards white, male scholars and research from the Global North and set this in the context of an exploration of decolonising their curriculum.

Suchan Bird and Pitman examined reading lists in an undergraduate science module on genetics methodology and a postgraduate social science module on research methods to be dominated by white, male, and Eurocentric authors, although on the social science reading list equal proportions of the authors were male and female, and almost a third of authors on the science list identified as Asian. They discussed implications for the growing interest in decolonising curricula across a range of disciplines and institutions.

Within Africa, attention is being paid to decolonising education. Ifejola Adebisi has provided a thoughtful review:

‘Essentially, people in Africa have inadequate knowledge of Africa because the inherited colonial systems were not designed to enable them to acquire such knowledge. And people who are outside Africa, who determine what amounts to good knowledge, know even less. Decolonial thought requires us to build global structures that allow all knowledges to equally complete our understanding of the world.’

This is echoed in ‘Gender, knowledge production, and transformative policy in Africa’ where N’Dri Thérèse Assié-Lumumba argues that:

‘Contemporary formal African education has been deficient since its inception as it was designed to negate, suppress, and eliminate African culture, promoting inadvertent and deliberate “epistemicide”... In its philosophy, this received system was also gendered and unequal, with limited access and a less valued curriculum designed for the female population.’

Zimbabweans Thondhlana and Garwe in their introduction to the supplementary issue of the Journal of the British Academy ‘Repositioning of Africa in knowledge production: shaking off historical stigmas’ concluded that the high quality of the articles ‘...showcases our conviction that Africa can indeed shake off historical stigmas and reposition itself as a giant in knowledge production.’

How will distributing knowledge creation work?

Structural change

In an earlier section of this course, we discussed the notion of the ‘distributed university’ - which provides education largely online to ‘where it is needed, reducing local and global inequalities in access, and emphasising local relevance’. This structure could also be relevant to distributing knowledge creation, in addition to knowledge dissemination. Following the notion of a focus on online education with infrastructure being distributed away from central inner-city campuses towards regional hubs, a similar structure would encourage knowledge creation among the populations to which the education is distributed. The distributed model would encourage co-creation of knowledge - through collaboration with local communities, industries, minority groups and geographic regions (local, regional and international).

Co-creation of knowledge

Knowledge co-creation has been defined by the OECD as ‘the process of the joint production of innovation between industry, research and possibly other stakeholders, notably civil society’. OECD identifies four factors that are essential for successful co-creation: engagement with stakeholders; effective governance and operational management structures; agreement on ownership and intellectual property, and adjustment for changing environments. Although the OECD report focuses on science, technology and industry, these concepts are applicable to education.

There is a substantial literature about students learning together and co-creating knowledge and a whole journal is devoted to ‘students as partners in learning and teaching in higher education’. Lay involvement in co-production of knowledge also has potential, and may include citizen science projects.

Publication

Even if knowledge creation is distributed among populations and groups currently under-represented, this does not lead automatically to greater publication of that knowledge. A desirable goal would be that publication of the knowledge produced should be accessible both to the scientific community and the potential users of it. In a later section of this course, we discuss the potential for open publishing of research and as for research, open access to educational materials through Open Educational Resources (OER).

Incorporation into educational programmes

As for publication of research, structures and incentives will be needed that encourage the incorporation of knowledge generation into educational programmes. Distributing knowledge creation is a necessary step in the process of curriculum decolonisation – an area that is becoming increasingly discussed among universities in the Global North. Consideration also needs to be given to how to increase the diversity of academic staff to include those who come from, and reflect the issues of, currently neglected populations. Going beyond the traditional academic community in educational programme development has been shown to be possible, and Community Open Online Courses are an example of the benefits of widening the range of who is involved in producing educational programmes.

Building capacity

It will be important to build capacity for each of the three themes that run through this part of the course:

Research capacity building should be localised among populations with current low capacity,

Mary Ann Lansang and Rudolfo Dennis have clearly articulated the issue from a health perspective

‘For developing countries to indigenize health research systems, it is essential to build research capacity... As a key element of capacity building, countries must also address issues related to the enabling environment, in particular: leadership, career structure, critical mass, infrastructure, information access and interfaces between research producers and users. The success of efforts to build capacity in developing countries will ultimately depend on political will and credibility, adequate financing, and a responsive capacity-building plan that is based on a thorough situational analysis of the resources needed...’

The paper (quoted earlier in this section) Decolonising research capacity development, which is a nice summary of the more detailed paper ‘Capacity for what? Capacity for whom?’ A decolonial deconstruction of research capacity development practices in the Global South and a proposal for a value-centred approach, suggests that research capacity development should be based on knowledge justice, systems thinking and localisation. The paper goes on to say that strengthening knowledge production alone is not enough and fair access to the knowledge created requires collaboration between:

‘The institutions tasked with creating knowledge (eg., universities and think tanks); The institutions tasked with translating knowledge (eg., industry and government); and The governance institutions tasked with enabling the process, through appropriate regulatory frameworks and infrastructure.’ and ‘Localising research capacity development: True localisation means shifting power so that ideas are developed in local communities, to address their own needs. This requires systems and processes of knowledge production that are not vulnerable to external interests. Because these interests are usually leveraged through foreign investment, localisation can only be achieved by breaking the reliance on international research funding. Clearly, local financing is a political decision that each country must make independently – do they encourage home-grown knowledge production or continue relying on international organisations? Enhancing the demand for local knowledge requires cultural and societal change to overcome the deficit mindset.’

Development of publishing options for researchers in under-represented populations and groups.

An example of this is a coalition led by the West and Central African Research and Education Network (WACREN). The aim is to build both capacity for peer reviewing among African Public Health researchers though online courses and the development of new open publishing options through repositories for preprints and open reviews.

Creation of educational resources.

There is considerable activity in building capacity for the creation and use of Open Educational Resources (OER) - a key component for distributing education more widely as we discuss in a later section of this course. As an example, one of the recommendations of a UNESCO report includes: ‘developing the capacity of all key education stakeholders to create, access, re-use, re-purpose, adapt, and redistribute OER.’ This is in the context of one of the report’s stated aims: ‘One key prerequisite to achieve SDG 4 is sustained investment and educational actions by governments and other key education stakeholders, as appropriate, in the creation, curation, regular updating, ensuring of inclusive and equitable access to, and effective use of high quality educational and research materials and programmes of study.’ [Note: SDG 4 relates to Sustainable Development Goal number 4 ‘Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all.’ While on the topic of SDGs, a plea has been made to broaden the knowledge base in an editorial titled ‘We urgently need multiple knowledges to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals’]

Of course the main aim of this course is to help develop capacity among academics and collaborative partners, through discussing the theory and practice of distributing both the dissemination of knowledge as well as the creation of knowledge.

-

Please reflect on the extent of any biases in knowledge creation in your own subject areas and how you might be able to stimulate knowledge creation to capture the voices of under-represented populations

-

Following this section on Open access to educational resources and research - you should be able to:

Describe the evolution and potential role of Open Educational Resources for education and the critical importance of open access to distributing learning.

Critically evaluate the impact of open access on equity in access to education.

Identify and explain initiatives that leverage distributed and networked learning to bridge gaps in educational access and outcomes.

Principles and background

Open education is critical to the pursuit of equity in access to knowledge through the distribution of education and knowledge production. The underlying principle of open education is nicely stated by McGreal as ‘publicly-funded research and educational content belongs to the people and should therefore be open and accessible to them.’ He links this to Sustainable Development Goal number 4: ‘Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all.’

Open education is defined as encompassing ‘resources, tools and practices that employ a framework of open sharing to improve educational access and effectiveness worldwide.’ So ‘Open Education combines the traditions of knowledge sharing and creation with 21st century technology to create a vast pool of openly shared educational resources, while harnessing today’s collaborative spirit to develop educational approaches that are more responsive to learner’s needs.’

There are many components of openness, as described by UNESCO as Open Solutions: ‘Open Solutions, comprising Open Educational Resources (OER), Open Access to scientific information (OA), Free and Open Source Software (FOSS) and Open Data, have been recognized to support the free flow of information and knowledge, thereby informing responses to global challenges.’

This intersects with the UNESCO definition of Open Science: ‘Open science is a set of principles and practices that aim to make scientific research from all fields accessible to everyone for the benefits of scientists and society as a whole. Open science is about making sure not only that scientific knowledge is accessible but also that the production of that knowledge itself is inclusive, equitable and sustainable.’

Here, we are going to focus on Open Educational Resources (OER), and Open Educational Practices (OEP) that underpin the applications of open education in practice.

Open Educational Resources (OER)

A nice 2024 summary, Open educational resources can address inequalities in HE, provides the context: ‘Despite significant progress in expanding global access to higher education, profound inequalities persist. Teaching and learning resources remain prohibitively expensive, creating financial burdens and retention barriers for students. Furthermore, paywalled, copyrighted content limits academics’ ability to adapt materials for local relevance, particularly in the Global South.’

The above article also outlines the evolution of the OER movement and quotes UNESCO’s 2012 Paris OER Declaration: OERs are “teaching, learning and research materials in any medium, digital or otherwise, that reside in the public domain or have been released under an open licence that permits no-cost access, use, adaptation and redistribution by others with no or limited restrictions”. The article also quotes The 5Rs of Openness:

The 5Rs of Openness Retain – the right to make, own, and control copies of the content

Reuse – the right to use the content in a wide range of ways (e.g., in a class, in a study group, on a website, in a video)

Revise – the right to adapt, adjust, modify, or alter the content itself (e.g., translate the content into another language)

Remix – the right to combine the original or revised content with other open content to create something new (e.g., incorporate the content into a mashup)

Redistribute – the right to share copies of the original content, your revisions, or your remixes with others (e.g., give a copy of the content to a friend)

Broadening the scope of Open Educational Resources (OER)

Most of the resources that come under the heading of Open Educational Resources (OER) are individual resources used in the educational process. The paper Plan E for Education: open access to educational materials created in publicly funded universities makes the case for open access to include whole or sections of courses including assessments, not just isolated resources.

Open Access to research

As well as resources designed for educational programmes, many of the resources included under the OER banner are scientific research articles published as open access (OA). This is nicely described on the Open Education Global website: ‘In addition to teaching and learning materials, open education includes research outputs. Open Access (OA) refers to research published in a way that is digital, online, free of charge, and free of most copyright and licensing restrictions. OA removes price barriers such as subscriptions and pay-per-view fees giving researchers, students, and public access to research. As most research is publicly funded OA ensures the public has access to what is funded. OA makes research discoverable, available and reproducible for the advancement of science. When used for teaching and learning Open Access articles are a form of OER.’

Open licences

The principles of openness, as identified in the 5 Rs, require appropriate copyright licences to publish the material. Creative Commons licences have been developed for this purpose: ‘Creative Commons licenses give everyone from individual creators to large institutions a standardized way to grant the public permission to use their creative work under copyright law. From the reuser’s perspective, the presence of a Creative Commons license on a copyrighted work answers the question, What can I do with this work?’ Creative Commons (CC) licences come in six different forms, from most to least permissive. This course is licenced under CC licence BY 4.0 – so you are free to share and adapt the material for any use, even commercial.

Here is a short video - Importance of Open Licences for OER.

Open Educational Practices

The term Open Educational Practices has been created to allow Open Educational Resources (OER) to be put into practice. Cronin defines Open Educational Practices as ‘collaborative practices that include the creation, use, and reuse of OER, as well as pedagogical practices employing participatory technologies and social networks for interaction, peer-learning, knowledge creation, and empowerment of learners.’ Not really included in this definition are the technology infrastructure, the institutional regulatory framework to encourage or inhibit openness nor the structural requirements for distributed delivery and knowledge creation. There is much discussion about definitions, but rather than enter the debate we have identified some of the issues below. Along this theme, the term Open Pedagogy is also used, as in this paper What is Open Pedagogy? - here we consider the term to be the same as Open Educational Practices, and will not discuss further.

Open educational technology infrastructure

In the section of this course on educational technologies, we discussed the issue of knowledge surveillance, where proprietary educational software programmes are used by EdTech companies to collect and monetise data. As summarised in Digital infrastructures for education: Openness and the common good ‘adoption of proprietary platforms centred on the massive collection and processing of behavioural data and works generated by educational actors by private, for-profit corporations is antithetical to the ethos of education and the common good.’ The same article makes the case for the principles of Open Education to be applied to the development of educational infrastructure to preserve the principles of the common good in education.

Repositories and open access to courses

As long ago as 2002, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) published 50 of their courses freely online, now extended to all their courses. Others have followed the lead, and there are a number of repositories of open educational materials. MERLOT (Multimedia Educational Resource for Learning and Online Teaching) is an international community of educators, learners and researchers offering free access to more than 99,000 curated online learning and support materials and content creation tools. The further development of repositories will be important to support open access as a key aspect of distributed education. We discuss repositories as important components of a distributed learning ecosystem in the digital technologies section of this course.

Collaboration and sharing

Openness depends on collaboration and sharing in the creation and use of educational resources, and collaborative practices were identified above as part of the definition of Open Educational Practices. Abegglen and colleagues have proposed the addition of collaboration as a central element to education, with openness as a prerequisite and an antidote to the neoliberal competitive approach to education. While this may be a utopian goal, there are still opportunities for, as well as great examples of, collaboration in today’s higher education system.

Structural and regulatory issues

Institutional support is required for the development and use of OER. Given the competitive business model that underpins higher education in many countries, most university courses and their material remain behind paywalls for the exclusive use of enrolled students.

Funders of research have led the drive to make research findings openly available as open access (OA), with many funding organisations requiring the publication of papers resulting from funded research to published as open access. Plan S is ‘…an initiative for Open Access publishing that was launched in September 2018. The plan is supported by cOAlition S, an international consortium of research funders. Plan S requires that, from 2021, scientific publications that result from research funded by public grants must be published in compliant Open Access journals or platforms.’ The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation have now added to this requirement that they will not pay for Article Processing Charges which many journals require to allow open access to their articles. This is a whole extra topic, including the requirement for open access preprints and alternative publishing options, and beyond the scope of the course.

As mentioned above, Plan E has been conceived as an educational equivalent of Plan S, in which ‘a proportion of the educational resources generated in publicly funded universities be made freely available for sharing and use by others. Thus, high quality education, produced through public funding, could be made available to other universities and individual autodidacts and for the development of innovative educational delivery methods.’ Support for this initiative is yet to be realised however and it remains an idea!

Plan E also suggests ‘a peer review system for educational materials to mirror that already used for research publications. Academic credit could then flow to those who publish and review educational resources and extend to other academic input such as updating the work and creating instructional materials.’ This might help to remove the bias against teaching and towards research, found in many universities, and which is also a barrier to the adoption of open education.

In the section on the concepts of distributed education at the start of this course, we identified some of the structural enablers of distributing education, such as local or virtual hubs. This goes to the point that to increase the scale, system change is required including the interaction between the principles and practices of openness and the institutional, regulatory and structural requirements of a distributed approach.

Need for advocacy

Institutional and national barriers to open education will need to be removed if we are to make access to education truly equitable. We hope that users of this course will see the need and advocate for this change.

-

Please reflect on the potential of, and the barriers to, the increased use of Open Educational Resources in your own setting.

-

By the end of this section of the course you should be able to:

Discuss the importance of using best practice online education rather than just moving face-to-face teaching online.

Demonstrate the ability to collaborate in the design of materials that can be used in distributed and networked learning programmes.

Develop assessment tools and implementation strategies that align with the goals of distributed and networked learning.

Discuss the ethical implications of distributed and networked learning, including data privacy, digital equity, and the digital divide.

Best practice online education.

Online education holds considerable potential for broadening access to higher education and diversifying the student population. Online technologies offer the flexibility to learn from anywhere, at any time, and from a diverse range of instructors and also facilitate enhanced collaboration, both globally and locally.

Online teaching has been around for many years, and an increasing trend has occurred both in the formal higher education sector and outside it. This increasing trend accelerated when the Covid pandemic pushed most universities to switch to online from their usual face-to-face mode. This led to two competing outcomes. First, the potential of the online mode has been realised to become the ‘new normal’ in higher education – most often in a hybrid model together with face-to-face teaching. Second, those universities who did not have experience or infrastructure to support online teaching just put their lectures online often with poor student feedback. There is a big difference between emergency remote teaching and online learning. Caroll and Conboy make the point that it is important to ‘normalise the new normal’ to make sure that organisations adapt appropriately to the increased reliance on technology.

Online education requires its own educational theory to guide practice. In 2016 Tony Bates published The 10 Fundamentals of Teaching Online for Faculty and Instructors, and updated it twice. He makes a number of points, including:

‘An online learner is usually studying in an isolated situation, without other students or the instructor physically present. There are many ways to overcome the isolation of the online learner …, but giving them recordings of 50-minute classroom presentations is not one of them.’

and lists many advantages including:

‘Most instructors… find a time shift when they move to online teaching. The more time you put into the development of the course… the less time you find yourself spending on content during the delivery of the course, because it is already there.’

By the way, there have been many reviews of comparisons between online and face-to-face teaching. As mentioned above, comparing face-to-face teaching before Covid with emergency remote teaching is not an appropriate comparison. Most appropriate reviews conclude that there is no systematic difference in outcome between the two. However, as well as the benefits outlined by Bates and others above, the advantages we list during this course that come from distributing learning are dependent on the online delivery mode. Of course, regard to best practice and meeting the needs of students for knowledge and skills are crucial for both online and face-to-face education.

Most often, the set-up of online learning also requires students to work autonomously and auto-didactically. This places a high responsibility on both the student and the teacher to ensure students are well equipped to manage, pace, and advance their own learning and performance. Interaction and guidance rubrics can be a critical support for the student and the instructor to facilitate and guide self-paced training. Self assessment rubrics can enable students to monitor and direct their own learning and student co-creation of assessment rubrics may be associated with improved learning outcomes.

Designing online learning for asynchronous courses requires careful consideration to ensure that the learning experience is engaging, accessible, and effective. Here's a table summarizing the best practices for designing asynchronous online learning - of course these are relevant to any type of education:

Characteristic

Explanation

Clear Learning Objectives

Define and communicate clear learning objectives for each module, aligning all activities and assessments accordingly.

Structured and Consistent Layout

Use a consistent course layout to facilitate navigation, with clear sections like introduction, content, and assessments.

Chunking Content

Break down content into smaller, manageable pieces to prevent cognitive overload and enhance learning retention.

Engaging and Varied Content

Incorporate multimedia (videos, podcasts) and interactive elements (quizzes, discussions) to cater to diverse learning styles.

Accessible and Inclusive Design

Ensure all materials are accessible, including captions, transcripts, and screen reader compatibility for inclusivity.

Opportunities for Interaction and Reflection

Integrate interactive activities like forums, peer reviews, and reflective journaling to enhance engagement.

Clear Instructions and Expectations

Provide detailed instructions and communicate expectations for participation, assignments, and deadlines.

Frequent, Low-Stakes Assessments

Use quizzes, self-checks, and reflections to help students monitor progress without high-pressure assessments.

Scaffolded Learning Path

Design learning experiences that build on previous knowledge, moving from simple to more complex concepts.

Feedback Mechanisms

Offer timely, constructive feedback on activities, using both automated and personalized feedback methods.

Flexible Pacing

Allow students some control over pacing while maintaining structure with deadlines to accommodate various learning speeds.

Support Resources

Provide access to extra resources, tutorials, and tech support to help students succeed independently.

Community Building

Foster a sense of community through regular communication, peer interaction, and introductory activities.

Regular Check-ins and Updates

Use announcements and reminders to keep students informed and maintain engagement throughout the course.

Use of Analytics for Improvement

Monitor engagement and performance data to make informed adjustments to content and support as needed.

Programme design

Based on a review of the literature, Stracke and colleagues have outlined typologies of online courses relevant to distributed learning, and the table below outlines their framework which can be used for course design:

From Stracke et al. under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

It is clear from the table above that course content is only one part of the work that needs to be done when thinking about how to design a programme. Going further, there are a number of other areas to consider. You will have seen the figure below earlier in the course (it first appeared in Distributing knowledge creation to include under-represented populations in The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning (in press)). As we design our course, we will have to think about each aspect of the framework: for example how will the course fit into a distributed structure and meet policy requirements, and what collaborations will be required?

Note: some of the components of the framework are core requirements for distributing education, while others might be options. This is to indicate that even those institutions who are not prepared to embrace the benefits of openness, collaboration and distributed knowledge creation can be encouraged to participate in distributing education within a limited context. Attention to each of the components of the whole framework, however, is required to achieve the full benefits of distributed education and knowledge creation.

Case studyTwo of the authors of this course were involved in the development of an online course CanadARThistories which met most of the criteria in the diagram above. As you will see if you explore the website, this was a collaboration between 5 Canadian universities, using best practice online development, and published under a Creative Commons licence. It met a societal need to put the history of art in Canada in the context of the social and historical development of the country. It offered ways in which the course could be distributed widely. Assessment and certification.

There has been debate about the assessment process in online education. The many benefits include the ability to offer rapid feedback to large numbers of students, such as through multiple choice questions with automated feedback. The most common concern is about how to maintain the academic integrity of the assessment process and avoid cheating. However there are a number of other issues that should be taken into account when considering best practice in the assessment process. A literature review and survey of educators identified key design considerations for online assessments: academic integrity; provision of quality feedback; positive learning experience for students; assure the integrity of student information; ensure all students have an equal chance to complete the assessment successfully; and authenticity. A meeting of experts convened by JISC, identified five ways technology could help by making assessments: authentic, accessible, appropriately automated, continuous and secure. Authenticity is clearly important, preferably to serve a public purpose, and the creation of lay summaries of key principles is one way of achieving this.

This is a large topic, and may be discipline specific – we want to emphasise the importance to ensuring best practice in the assessment process that is relevant to, and takes advantage of, the online format.

A note on certification. This course offers an automated certificate of completion, based on having accessed some of the key resources and posted reflections to the forums. However those organisations who take advantage of the Creative Commons licence under which the course is published are able to re-purpose the course to their own requirements, including different certification methods.

Ethical implications of distributed education

1. Copyright issues and Open Educational Resources (OER). Most distributed education will utilise Open Educational Resources (see section 3 of this course). There are copyright issues in using the material produced by others, and there are two main areas for us to consider.

The issue of ‘fair use’. The publication Code of Best Practices in Fair Use of OER tells us ‘The good news for OER is that intellectual property law, and copyright in particular, operate as less of a meaningful constraint on otherwise sound pedagogical practice than is generally understood.’ The Code advises courses to include this statement as a signal: ‘Unless otherwise indicated, third-party texts, images, and other materials quoted in these materials are included on the basis of fair use as described in the Code of Best Practices for Fair Use in Open Education.’

Copyright Compliance for Open Educational Resources (OER) Explained is worth exploring for more information. It explains what is covered by ‘fair use’:

Using excerpts of copyrighted material for teaching, scholarship, and research purposes. This includes quoting passages from books or articles, displaying chart or images, etc.

Typically less than 10-20% of a copyrighted work can be used without permission under fair use.

Factors like the nature of use (educational vs commercial), amount used, and potential market impact are also considered.

The issuing of Creative Commons licences, which provide permission for the use of resources according to various criteria. Most OER are actually published under a Creative Commons Licence which provides permission for the use of the work under copyright law. There are a number of different licences varying in permissiveness which identify what a user can do with the work. For example, this course is published under the least restrictive of the licences https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ which allows the reader to share and adapt the material, provided appropriate attribution is made to the creator of the resource. [Note: the CC0 licence is even less restrictive and waives all rights.]

Here is a brief video explaining the different licenses and what they mean

2. Digital equity and the digital divide. An editorial to introduce a special issue of the Australasian Journal of Educational Technology summarises the issue clearly: ‘Digital equity is a complex and multifaceted concept. It includes not only access to hardware, software, and connectivity to the Internet but also meaningful, high-quality, and culturally relevant content in local languages, and the ability to create, share, and exchange knowledge. Participatory citizenship in the digital era involves the right to access and participate in higher education. Indeed, it is a key civil rights issue of the modern world.’

As mentioned in the Introduction to this course, there are many inequities in access to higher education. As we move to the online mode it may be that despite our efforts to reduce these inequities through distributing education online, the digital divide might introduce its own inequity. This can apply to those who are not enabled to get into universities, to students once they have entered their studies and also to the teachers themselves.