Section 6. Designing programmes which incorporate distributed and networked education

Résumé de section

-

By the end of this section of the course you should be able to:

Discuss the importance of using best practice online education rather than just moving face-to-face teaching online.

Demonstrate the ability to collaborate in the design of materials that can be used in distributed and networked learning programmes.

Develop assessment tools and implementation strategies that align with the goals of distributed and networked learning.

Discuss the ethical implications of distributed and networked learning, including data privacy, digital equity, and the digital divide.

Best practice online education.

Online education holds considerable potential for broadening access to higher education and diversifying the student population. Online technologies offer the flexibility to learn from anywhere, at any time, and from a diverse range of instructors and also facilitate enhanced collaboration, both globally and locally.

Online teaching has been around for many years, and an increasing trend has occurred both in the formal higher education sector and outside it. This increasing trend accelerated when the Covid pandemic pushed most universities to switch to online from their usual face-to-face mode. This led to two competing outcomes. First, the potential of the online mode has been realised to become the ‘new normal’ in higher education – most often in a hybrid model together with face-to-face teaching. Second, those universities who did not have experience or infrastructure to support online teaching just put their lectures online often with poor student feedback. There is a big difference between emergency remote teaching and online learning. Caroll and Conboy make the point that it is important to ‘normalise the new normal’ to make sure that organisations adapt appropriately to the increased reliance on technology.

Online education requires its own educational theory to guide practice. In 2016 Tony Bates published The 10 Fundamentals of Teaching Online for Faculty and Instructors, and updated it twice. He makes a number of points, including:

‘An online learner is usually studying in an isolated situation, without other students or the instructor physically present. There are many ways to overcome the isolation of the online learner …, but giving them recordings of 50-minute classroom presentations is not one of them.’

and lists many advantages including:

‘Most instructors… find a time shift when they move to online teaching. The more time you put into the development of the course… the less time you find yourself spending on content during the delivery of the course, because it is already there.’

By the way, there have been many reviews of comparisons between online and face-to-face teaching. As mentioned above, comparing face-to-face teaching before Covid with emergency remote teaching is not an appropriate comparison. Most appropriate reviews conclude that there is no systematic difference in outcome between the two. However, as well as the benefits outlined by Bates and others above, the advantages we list during this course that come from distributing learning are dependent on the online delivery mode. Of course, regard to best practice and meeting the needs of students for knowledge and skills are crucial for both online and face-to-face education.

Most often, the set-up of online learning also requires students to work autonomously and auto-didactically. This places a high responsibility on both the student and the teacher to ensure students are well equipped to manage, pace, and advance their own learning and performance. Interaction and guidance rubrics can be a critical support for the student and the instructor to facilitate and guide self-paced training. Self assessment rubrics can enable students to monitor and direct their own learning and student co-creation of assessment rubrics may be associated with improved learning outcomes.

Designing online learning for asynchronous courses requires careful consideration to ensure that the learning experience is engaging, accessible, and effective. Here's a table summarizing the best practices for designing asynchronous online learning - of course these are relevant to any type of education:

Characteristic

Explanation

Clear Learning Objectives

Define and communicate clear learning objectives for each module, aligning all activities and assessments accordingly.

Structured and Consistent Layout

Use a consistent course layout to facilitate navigation, with clear sections like introduction, content, and assessments.

Chunking Content

Break down content into smaller, manageable pieces to prevent cognitive overload and enhance learning retention.

Engaging and Varied Content

Incorporate multimedia (videos, podcasts) and interactive elements (quizzes, discussions) to cater to diverse learning styles.

Accessible and Inclusive Design

Ensure all materials are accessible, including captions, transcripts, and screen reader compatibility for inclusivity.

Opportunities for Interaction and Reflection

Integrate interactive activities like forums, peer reviews, and reflective journaling to enhance engagement.

Clear Instructions and Expectations

Provide detailed instructions and communicate expectations for participation, assignments, and deadlines.

Frequent, Low-Stakes Assessments

Use quizzes, self-checks, and reflections to help students monitor progress without high-pressure assessments.

Scaffolded Learning Path

Design learning experiences that build on previous knowledge, moving from simple to more complex concepts.

Feedback Mechanisms

Offer timely, constructive feedback on activities, using both automated and personalized feedback methods.

Flexible Pacing

Allow students some control over pacing while maintaining structure with deadlines to accommodate various learning speeds.

Support Resources

Provide access to extra resources, tutorials, and tech support to help students succeed independently.

Community Building

Foster a sense of community through regular communication, peer interaction, and introductory activities.

Regular Check-ins and Updates

Use announcements and reminders to keep students informed and maintain engagement throughout the course.

Use of Analytics for Improvement

Monitor engagement and performance data to make informed adjustments to content and support as needed.

Programme design

Based on a review of the literature, Stracke and colleagues have outlined typologies of online courses relevant to distributed learning, and the table below outlines their framework which can be used for course design:

From Stracke et al. under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

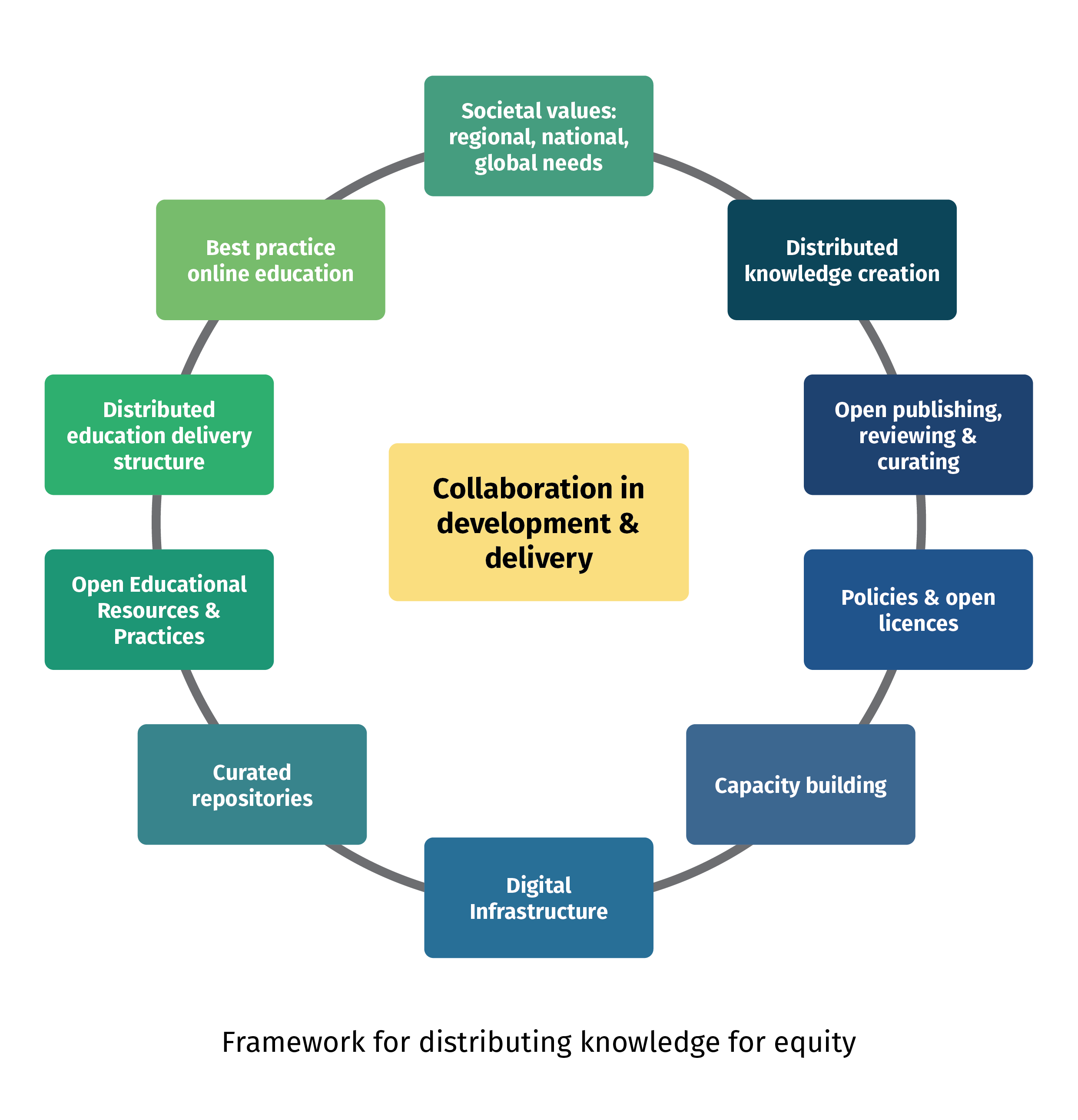

It is clear from the table above that course content is only one part of the work that needs to be done when thinking about how to design a programme. Going further, there are a number of other areas to consider. You will have seen the figure below earlier in the course (it first appeared in Distributing knowledge creation to include under-represented populations in The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning (in press)). As we design our course, we will have to think about each aspect of the framework: for example how will the course fit into a distributed structure and meet policy requirements, and what collaborations will be required?

Note: some of the components of the framework are core requirements for distributing education, while others might be options. This is to indicate that even those institutions who are not prepared to embrace the benefits of openness, collaboration and distributed knowledge creation can be encouraged to participate in distributing education within a limited context. Attention to each of the components of the whole framework, however, is required to achieve the full benefits of distributed education and knowledge creation.

Case studyTwo of the authors of this course were involved in the development of an online course CanadARThistories which met most of the criteria in the diagram above. As you will see if you explore the website, this was a collaboration between 5 Canadian universities, using best practice online development, and published under a Creative Commons licence. It met a societal need to put the history of art in Canada in the context of the social and historical development of the country. It offered ways in which the course could be distributed widely. Assessment and certification.

There has been debate about the assessment process in online education. The many benefits include the ability to offer rapid feedback to large numbers of students, such as through multiple choice questions with automated feedback. The most common concern is about how to maintain the academic integrity of the assessment process and avoid cheating. However there are a number of other issues that should be taken into account when considering best practice in the assessment process. A literature review and survey of educators identified key design considerations for online assessments: academic integrity; provision of quality feedback; positive learning experience for students; assure the integrity of student information; ensure all students have an equal chance to complete the assessment successfully; and authenticity. A meeting of experts convened by JISC, identified five ways technology could help by making assessments: authentic, accessible, appropriately automated, continuous and secure. Authenticity is clearly important, preferably to serve a public purpose, and the creation of lay summaries of key principles is one way of achieving this.

This is a large topic, and may be discipline specific – we want to emphasise the importance to ensuring best practice in the assessment process that is relevant to, and takes advantage of, the online format.

A note on certification. This course offers an automated certificate of completion, based on having accessed some of the key resources and posted reflections to the forums. However those organisations who take advantage of the Creative Commons licence under which the course is published are able to re-purpose the course to their own requirements, including different certification methods.

Ethical implications of distributed education

1. Copyright issues and Open Educational Resources (OER). Most distributed education will utilise Open Educational Resources (see section 3 of this course). There are copyright issues in using the material produced by others, and there are two main areas for us to consider.

The issue of ‘fair use’. The publication Code of Best Practices in Fair Use of OER tells us ‘The good news for OER is that intellectual property law, and copyright in particular, operate as less of a meaningful constraint on otherwise sound pedagogical practice than is generally understood.’ The Code advises courses to include this statement as a signal: ‘Unless otherwise indicated, third-party texts, images, and other materials quoted in these materials are included on the basis of fair use as described in the Code of Best Practices for Fair Use in Open Education.’

Copyright Compliance for Open Educational Resources (OER) Explained is worth exploring for more information. It explains what is covered by ‘fair use’:

Using excerpts of copyrighted material for teaching, scholarship, and research purposes. This includes quoting passages from books or articles, displaying chart or images, etc.

Typically less than 10-20% of a copyrighted work can be used without permission under fair use.

Factors like the nature of use (educational vs commercial), amount used, and potential market impact are also considered.

The issuing of Creative Commons licences, which provide permission for the use of resources according to various criteria. Most OER are actually published under a Creative Commons Licence which provides permission for the use of the work under copyright law. There are a number of different licences varying in permissiveness which identify what a user can do with the work. For example, this course is published under the least restrictive of the licences https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ which allows the reader to share and adapt the material, provided appropriate attribution is made to the creator of the resource. [Note: the CC0 licence is even less restrictive and waives all rights.]

Here is a brief video explaining the different licenses and what they mean

2. Digital equity and the digital divide. An editorial to introduce a special issue of the Australasian Journal of Educational Technology summarises the issue clearly: ‘Digital equity is a complex and multifaceted concept. It includes not only access to hardware, software, and connectivity to the Internet but also meaningful, high-quality, and culturally relevant content in local languages, and the ability to create, share, and exchange knowledge. Participatory citizenship in the digital era involves the right to access and participate in higher education. Indeed, it is a key civil rights issue of the modern world.’

As mentioned in the Introduction to this course, there are many inequities in access to higher education. As we move to the online mode it may be that despite our efforts to reduce these inequities through distributing education online, the digital divide might introduce its own inequity. This can apply to those who are not enabled to get into universities, to students once they have entered their studies and also to the teachers themselves.

The map below, from Our World in Data shows the proportion of the population using the Internet in 2022. There are global inequities, and of course regional, socio-economic, gender and age differences in access within countries.

Sub-Saharan Africa has the lowest Internet usage, and despite the increasing use of mobile technology the paper Mobile learning policy and practice in Africa: Towards inclusive and equitable access to higher education finds ‘the formal integration of mobile learning in higher education to facilitate equitable access is very much in its infancy’ and recommends the ‘development of mobile learning policies needs to explicitly address and consider the intrinsic economic, social, regional, and gender inequalities existing within African countries.’

A study from Malaysia commented that the digital divide ‘extends far beyond mere accessibility to physical technologies such as devices and the Internet. The digital divide is also characterized by differences in motivation and attitudes towards technology, disparities in the acquisition of digital skills, levels of engagement in online activities, and, ultimately, inequalities in the outcomes achieved by individuals’. They found that the digital divide persists among Malaysian university students

The same issues apply to the teachers. A study in Pakistan identified a persistent Digital divide among higher education faculty at four levels: motivational, physical, skills, and usage.

Policy makers at the national and institutional levels will need to take account of these issues. A survey of higher education leaders in 24 countries explored the question Digital higher education: a divider or bridge builder? In relation to institutional ability to realise the potential of digital education, they emphasised the importance of collaboration: ‘Higher education leaders, especially those working in well-funded institutions, are uniquely positioned to spearhead collaborations in the digital sphere and build bridges across the gulfs of inequalities: by sharing their resources with other individuals and institutions, pushing the rhetoric about collaboration over individual gain, and creating awareness both internally and externally of hidden inequalities that can be tackled using digital technologies.’

Despite the presence of digital inequity, access to the Internet is increasing rapidly globally. Given this increase, and the attention the sector can to put to reduce the impact of the issue, we do not believe that the current digital divide should be used as a reason to deny the benefits of online learning. As time goes on, distributing education online is likely to offer the key to reducing global inequity in access to higher education.

Other ethical issues. There are a number of other issues relevant to online education which may raise ethical concerns about the programme. These might include accessibility barriers for people with disabilities or specific learning needs; potential for bias and inaccuracies in learning content; failure to give appropriate recognition to the sources of information and resources; and failure to offer appropriate student support and a sense of community among the students (and staff).

Collaboration through networks.

There are a number of networks that connect universities with each other. Mostly these involve individual academics within the universities collaborating with colleagues in research of common interest. Educational networks also exist, and these range from advocacy groups (such as the Australian Regional Universities Network) through networks who accredit each others’ courses (such as the OERu – who also offer shared infrastructure), to universities who collaborate on course design and delivery (such as iCollab and the Open Society University Network). Subject based networks are also developing, such as partnerships to achieve the educational goals in sustainability, whose authors make the point that ‘Co-developed curriculum is a collaborative process that involves multiple stakeholders and creates network structures with different nodes that provide links across different areas of the network. Forming collaborative networks requires disrupting many common approaches to education, especially in higher education institutions worldwide. Collaborative curriculum development involving networks of universities, industry, government, communities, and NPOs constitutes a mutually beneficial proposition that is agile but also disrupts the current education paradigms.’

The European Universities Initiative involves 41 university alliances, including almost 300 universities in the European region. Four critical dimensions have been identified in an examination of organisational potentials and perils: internal coordination, ways of resolving conflicts, commitment of member universities and cultural characteristics of the alliances. It is not clear how sustainable will these alliances be once EU funding ceases.

Networked education requires collaboration, and this is not always easy, and is counter to the way that many countries have structured their higher education systems using the competitive business model. However, there are many potential benefits, and we encourage the further exploration of collaboration among university networks to help realise the potential of distributed education and knowledge creation.

-

Please reflect on the main features of a distributed or networked education programme that you might design for your own setting.