Section 4. Distributing knowledge creation

الخطوط العريضة للقسم

-

By the end of this section of the course you should be able to:

Understand the differences and synergies between distributing knowledge dissemination and distributing knowledge creation

Reflect on the advantages of including under-represented individuals, communities and societies in the creation of knowledge

Describe the three main areas for distributing knowledge creation (research, research publications, and educational resources)

Consider some practical ways in which knowledge creation might be distributed to under-represented populations

Introduction

Note: Much of the content of this section is also to be found in the journal article 'Distributing knowledge creation to include under-represented populations' in The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning (in press).

We have already discussed the benefits of distributing education, that is the dissemination of knowledge, but before it is disseminated knowledge has to be created. This part of the course discusses the distribution of knowledge creation.

The reasons can be summarised as:

Research that incorporates the experience of distributed populations and population groups will give voice to to those groups and will have wider general applicability than research comes from limited populations.

Knowledge derived from research should be published and disseminated in ways that make it available to distributed populations to increase the likelihood that the research findings will be incorporated into policy and action across populations.

The incorporation of knowledge gained from distributed population groups into the educational experience will enrich it, and like the knowledge, make it more relevant to the whole population.

Three issues demonstrate the need for distributing knowledge creation

1. Research under-represents diverse populations.

Research on many topics can be enriched by the perspectives that come with the distribution of talent and representation of voices. Current research studies frequently exclude women, certain geographical areas (especially those in the Global South), and marginalised groups. For example, the lack of female and racial representation in the conduct of clinical trials in medicine diminishes the application of the research findings. Research in psychology and human behaviour has been criticised for focusing on western, educated, industrialised, rich, and democratic (WEIRD) societies. Oxford historian Peter Francopan, in his wide-ranging ‘The Earth Transformed: An Untold History’ (Francopan, 2023) writes:

‘Study of the past has been dominated by the attention paid to the ‘global north’...with the history of other regions often relegated to secondary significance or ignored entirely. That same pattern applies to climate science and research into climate history, where there are vast regions, periods and peoples that receive little attention, investment, and investigation...Much of history has been written by people living in cities, for people living in cities, and has focused on the lives of those who lived in cities.’

Hungarian social researcher Márton Demeter writes that

‘...the accumulation of academic capital is radically uneven with very high concentrations in a few core countries...the world of science can be separated for a few “winner” or core and many more “loser” or peripheral countries.’

He also quotes the observation that ‘loser-country scientists were cited less frequently than winner-country scientists, even in cases where they had been published in the very same journal.’

The philosophical concept of standpoint epistemology (or standpoint theory of knowledge) is relevant, and nicely boiled down by Georgetown University philosopher Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò as: 1) Knowledge is socially situated 2) Marginalized people have some positional advantages in gaining some forms of knowledge 3) Research programs ought to reflect these facts. Amy Allen, a liberal arts research professor of philosophy and women's, gender, and sexuality studies at The Pennsylvania State University, states: ‘Feminist standpoint theory has expanded beyond gender to encompass categories such as race and social class. Recent scholarship calls for studying standpoints of Third World groups in Western societies and marginalized groups in international contexts.’

Under-representation of indigenous peoples in research is now widely recognised. An example comes from the Arctic people:

‘Indigenous Peoples' knowledge systems hold methodologies and assessment processes that provide pathways for knowing and understanding the Arctic, which address all aspects of life, including the spiritual, cultural, and ecological, all in interlinked and supporting ways. For too long, Indigenous Peoples of the Arctic and their knowledges have not been equitably included in many research activities.’

In ‘Decolonizing knowledge production. Perspectives from the Global South’ representatives from India, Mexico, Brazil, Ghana and Tunisia discussed:

‘The production of knowledge in the global academic field is still highly unevenly distributed. Western knowledge, which originated in Western Europe and was deepened in the transatlantic exchange with North America, is still considered an often unquestioned reference in many academic disciplines. Thus, this specific, regional form of knowledge production has become universalized.’

In a supplementary issue of the Journal of the British Academy, Repositioning of Africa in knowledge production: shaking off historical stigmas, Crawford and colleagues summarise:

‘Contemporary debates on decolonising knowledge production, inclusive of research on Africa, are crucial and challenge researchers to reflect on the legacies of colonial power relations that continue to permeate the production of knowledge about the continent, its peoples, and societies.’

In trying to further understand the reasons, Maru Mormina and Romina Istratii ask and answer the question:

‘Why do many countries in the Global South remain behind when it comes to knowledge production and use, despite decades-long efforts to strengthen research capacity?

We think this is because the North still looks at the South with a ‘deficit mentality,’ according to which the latter has the problems and the former the solutions. From this standpoint, northern-led capacity development initiatives fail to recognise the South’s rich and diverse knowledge traditions and systems. Instead, they continue to impose monolithic blueprints of knowledge production, therefore re-inscribing colonial patterns of intellectual Western hegemony.”

A prestigious medical journal has followed this theme in The Lancet and colonialism: past, present, and future saying:

‘Institutions for knowledge production and dissemination, including academic journals, were central to supporting colonialism and its contemporary legacies ...Around the turn of the 20th century, The Lancet helped legitimise the field of tropical medicine, which was designed to facilitate exploitation of colonised places and people by colonisers...The Lancet must recognise and engage more with different methodologies of knowledge production, beyond the ways of knowing and the types of knowledge that it currently publishes...The Lancet must divest from the power of its centrality that makes it perpetuate various forms of colonialism.’

A case study - listening to patients An example of distributed knowledge creation is the initial identification of Long Covid which 'has a strong claim to be the first illness created through patients finding one another on Twitter: it moved from patients, through various media, to formal clinical and policy channels in just a few months.' 2. Research publications are biased towards the Global North

This bias is due both to lack of research capacity and biases in the publication system. Even when research is performed in these populations it may not be accessible to those who might apply the results. The relative lack of scientific publications by authors in the Global South has been widely discussed. Political scientists Medie and Kang report fewer than 3% of articles in four gender and politics journals published in the Global North were written by authors from the Global North. A geographical perspective on sub-Saharan Africa finds that digital content is even more unevenly geographically distributed than academic articles.

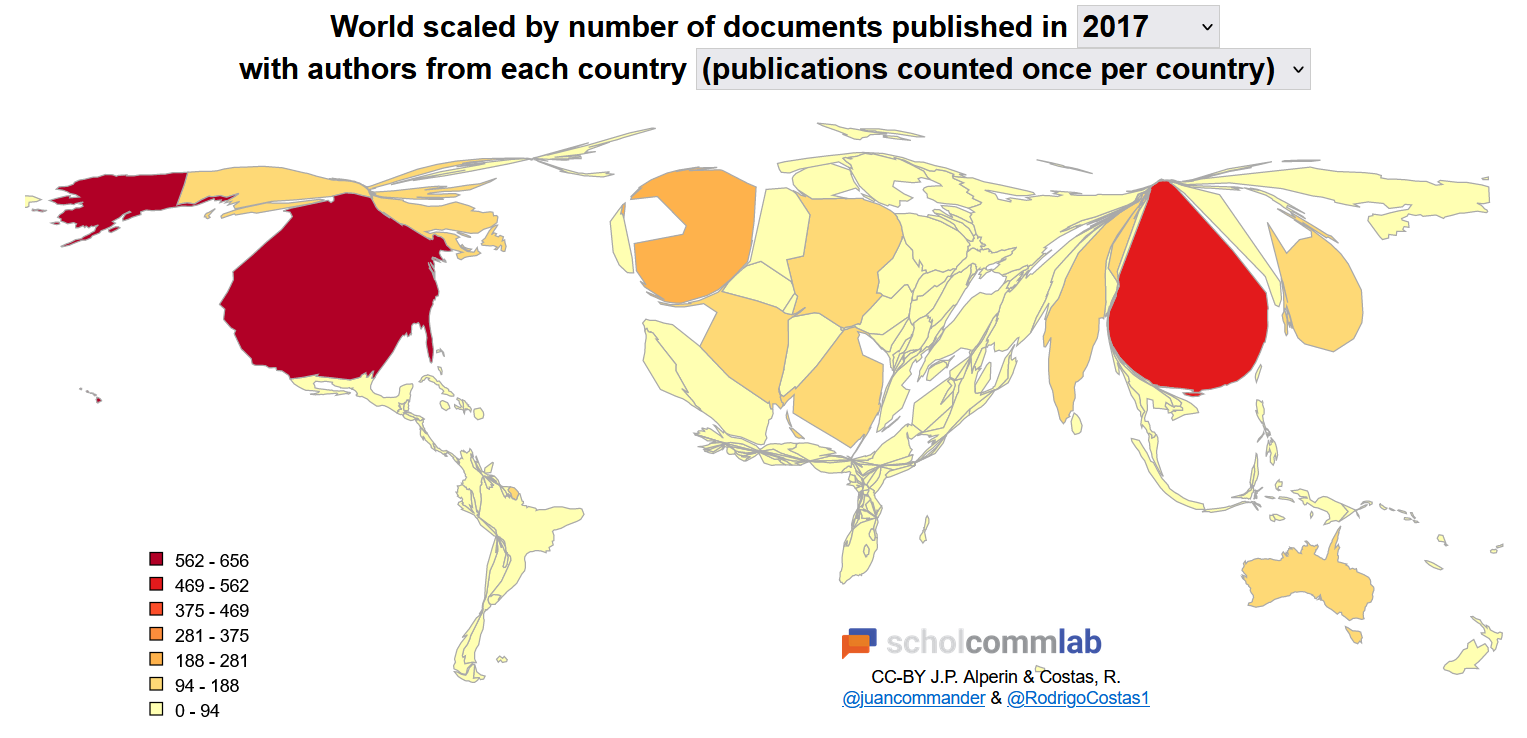

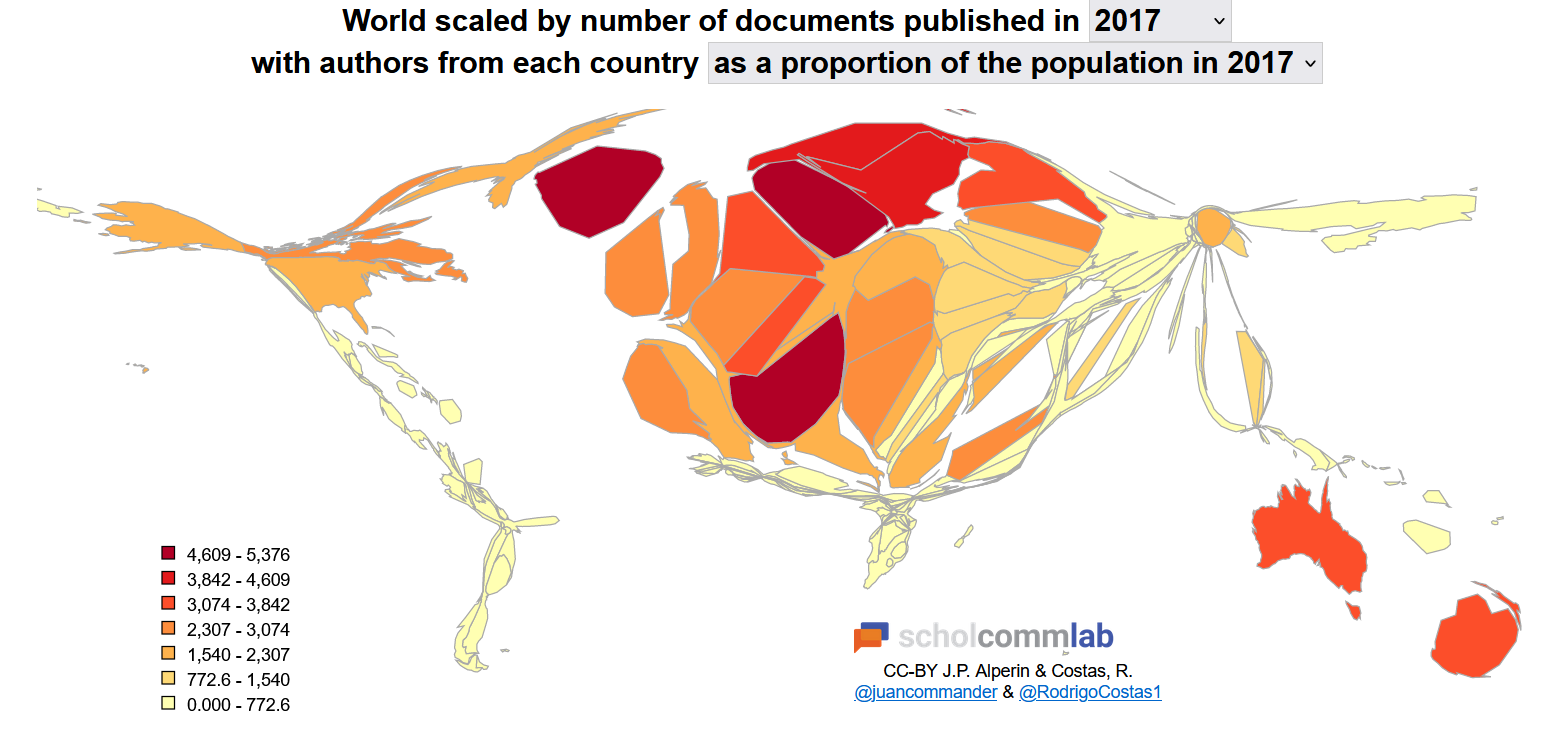

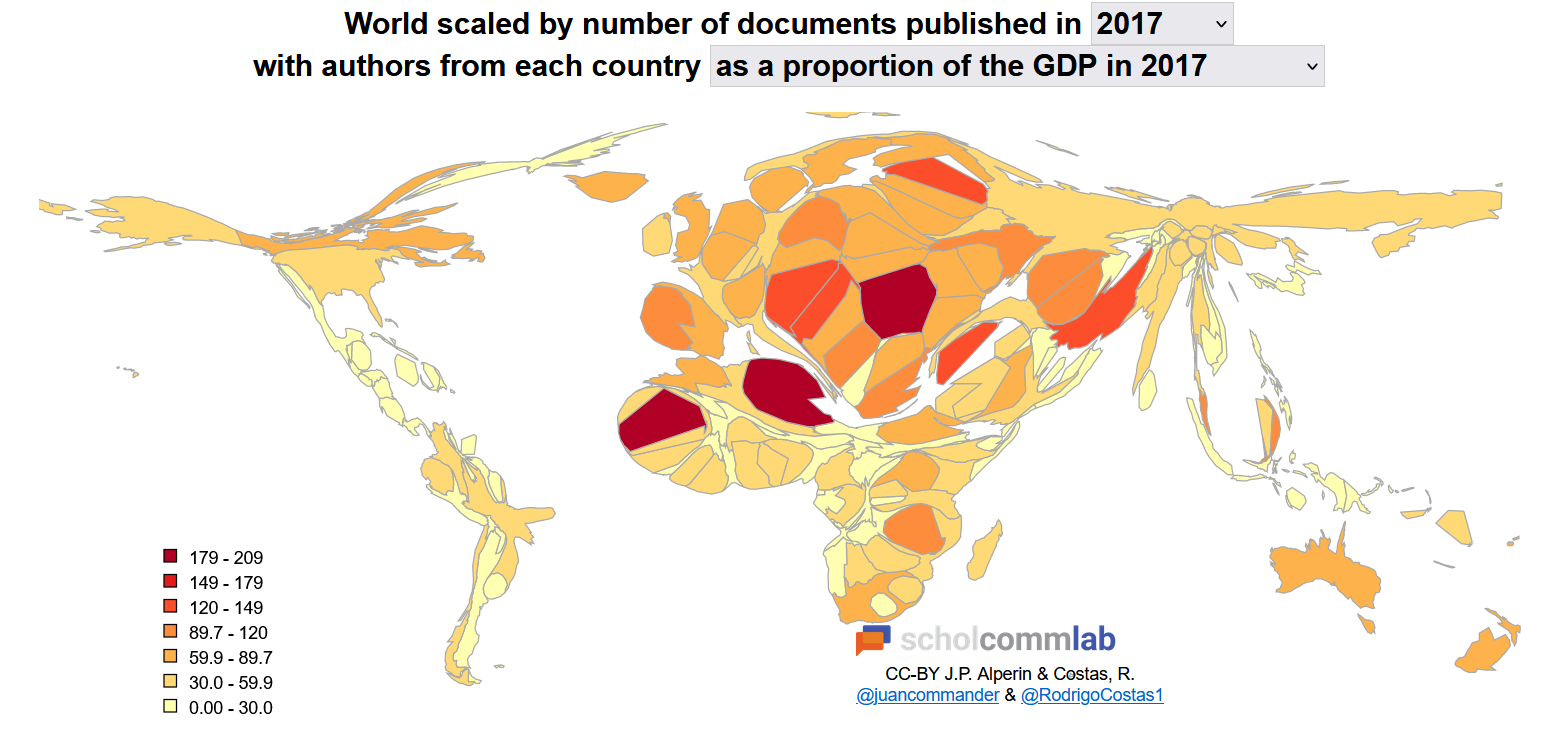

Three graphs scale the apparent size of each country by the number of documents cited in the Web of Science. When raw numbers are examined by country, there are gross global differences (Figure 1). These differences are attenuated when the numbers are adjusted for the population size of each country, (Figure 2). However, it is not until the figures are adjusted for GDP (Figure 3), that African countries at last become visible in the map.

The

patterns may underestimate the geographical disparities as the Web of

Science has

been criticised

for being structurally biased ‘against

research produced in non-Western countries, non-English language

research, and research from the arts, humanities, and social

sciences.’

Research

on health journals

published in 13 African countries found that most journals were not

indexed. Other valuable research may not appear in journals biased

against non-Global North sources. Article processing charges levied

on the authors or their institutions are further barriers to

publication.

The

patterns may underestimate the geographical disparities as the Web of

Science has

been criticised

for being structurally biased ‘against

research produced in non-Western countries, non-English language

research, and research from the arts, humanities, and social

sciences.’

Research

on health journals

published in 13 African countries found that most journals were not

indexed. Other valuable research may not appear in journals biased

against non-Global North sources. Article processing charges levied

on the authors or their institutions are further barriers to

publication. Research funding, and the research agenda that this funding meets, also favours the Global North, and where North-South research collaborations exist they are dominated by collaborators from the Global North. A study of Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTDs), which by their nature are endemic in low-to-middle-income countries, found that between the years 2007 and 2022 organisations in non-endemic countries received 75% of direct research funding on NTDs and 70% of indirect research funding on NTDs. An editorial in the SomaliHealth Action Journal (SHAJ) documents considerable dependence on external institutions and organisations, in particular North-American and European, on authorship, institutional affiliation and funding of published health research of relevance to Somalia. Most of the research of direct relevance to Somalia were authored by non-Somalis only, and did not address current and emerging health priorities for Somalia.

3. Educational resources are biased in the same way.

If population groups and geographical regions are are relatively under-represented in the research literature, educational examples from these populations are unlikely to find their way into the curriculum. This may be compounded by similar under-representation among the academic staff of educational institutions. Postian reviewed the courses at Villanova University and found that of the authors represented in undergraduate introductory courses, 70% were men, 90% worked in or originated from the Global North, and 7% were Black academic authors.

Ghai and colleagues audited recommended reading materials in the undergraduate curriculum for the psychological and behavioural sciences bachelor’s degree.

‘All first authors of primary research papers were affiliated with a university in a high-income country — 60% were from the United States, with 20% from the United Kingdom, 17% from Europe and 3% from Oceania. No author was affiliated with an institution based in Africa, Asia or Latin America. most of the research studies taught to undergraduates were also based on groups that were predominantly (67%) from the global north. Only 12% of articles included research participants from both the global north and the global south; no study in our reading lists focused on a group solely from the global south. Our syllabus lacked diversity even within the studies: less than 20% of articles reported diversity markers such as income or race, and only 3% mentioned participants’ urban or rural location.’

Tamimi and colleagues found their global health and social medicine curriculum biased towards white, male scholars and research from the Global North and set this in the context of an exploration of decolonising their curriculum.

Suchan Bird and Pitman examined reading lists in an undergraduate science module on genetics methodology and a postgraduate social science module on research methods to be dominated by white, male, and Eurocentric authors, although on the social science reading list equal proportions of the authors were male and female, and almost a third of authors on the science list identified as Asian. They discussed implications for the growing interest in decolonising curricula across a range of disciplines and institutions.

Within Africa, attention is being paid to decolonising education. Ifejola Adebisi has provided a thoughtful review:

‘Essentially, people in Africa have inadequate knowledge of Africa because the inherited colonial systems were not designed to enable them to acquire such knowledge. And people who are outside Africa, who determine what amounts to good knowledge, know even less. Decolonial thought requires us to build global structures that allow all knowledges to equally complete our understanding of the world.’

This is echoed in ‘Gender, knowledge production, and transformative policy in Africa’ where N’Dri Thérèse Assié-Lumumba argues that:

‘Contemporary formal African education has been deficient since its inception as it was designed to negate, suppress, and eliminate African culture, promoting inadvertent and deliberate “epistemicide”... In its philosophy, this received system was also gendered and unequal, with limited access and a less valued curriculum designed for the female population.’

Zimbabweans Thondhlana and Garwe in their introduction to the supplementary issue of the Journal of the British Academy ‘Repositioning of Africa in knowledge production: shaking off historical stigmas’ concluded that the high quality of the articles ‘...showcases our conviction that Africa can indeed shake off historical stigmas and reposition itself as a giant in knowledge production.’

How will distributing knowledge creation work?

Structural change

In an earlier section of this course, we discussed the notion of the ‘distributed university’ - which provides education largely online to ‘where it is needed, reducing local and global inequalities in access, and emphasising local relevance’. This structure could also be relevant to distributing knowledge creation, in addition to knowledge dissemination. Following the notion of a focus on online education with infrastructure being distributed away from central inner-city campuses towards regional hubs, a similar structure would encourage knowledge creation among the populations to which the education is distributed. The distributed model would encourage co-creation of knowledge - through collaboration with local communities, industries, minority groups and geographic regions (local, regional and international).

Co-creation of knowledge

Knowledge co-creation has been defined by the OECD as ‘the process of the joint production of innovation between industry, research and possibly other stakeholders, notably civil society’. OECD identifies four factors that are essential for successful co-creation: engagement with stakeholders; effective governance and operational management structures; agreement on ownership and intellectual property, and adjustment for changing environments. Although the OECD report focuses on science, technology and industry, these concepts are applicable to education.

There is a substantial literature about students learning together and co-creating knowledge and a whole journal is devoted to ‘students as partners in learning and teaching in higher education’. Lay involvement in co-production of knowledge also has potential, and may include citizen science projects.

Publication

Even if knowledge creation is distributed among populations and groups currently under-represented, this does not lead automatically to greater publication of that knowledge. A desirable goal would be that publication of the knowledge produced should be accessible both to the scientific community and the potential users of it. In a later section of this course, we discuss the potential for open publishing of research and as for research, open access to educational materials through Open Educational Resources (OER).

Incorporation into educational programmes

As for publication of research, structures and incentives will be needed that encourage the incorporation of knowledge generation into educational programmes. Distributing knowledge creation is a necessary step in the process of curriculum decolonisation – an area that is becoming increasingly discussed among universities in the Global North. Consideration also needs to be given to how to increase the diversity of academic staff to include those who come from, and reflect the issues of, currently neglected populations. Going beyond the traditional academic community in educational programme development has been shown to be possible, and Community Open Online Courses are an example of the benefits of widening the range of who is involved in producing educational programmes.

Building capacity

It will be important to build capacity for each of the three themes that run through this part of the course:

Research capacity building should be localised among populations with current low capacity,

Mary Ann Lansang and Rudolfo Dennis have clearly articulated the issue from a health perspective

‘For developing countries to indigenize health research systems, it is essential to build research capacity... As a key element of capacity building, countries must also address issues related to the enabling environment, in particular: leadership, career structure, critical mass, infrastructure, information access and interfaces between research producers and users. The success of efforts to build capacity in developing countries will ultimately depend on political will and credibility, adequate financing, and a responsive capacity-building plan that is based on a thorough situational analysis of the resources needed...’

The paper (quoted earlier in this section) Decolonising research capacity development, which is a nice summary of the more detailed paper ‘Capacity for what? Capacity for whom?’ A decolonial deconstruction of research capacity development practices in the Global South and a proposal for a value-centred approach, suggests that research capacity development should be based on knowledge justice, systems thinking and localisation. The paper goes on to say that strengthening knowledge production alone is not enough and fair access to the knowledge created requires collaboration between:

‘The institutions tasked with creating knowledge (eg., universities and think tanks); The institutions tasked with translating knowledge (eg., industry and government); and The governance institutions tasked with enabling the process, through appropriate regulatory frameworks and infrastructure.’ and ‘Localising research capacity development: True localisation means shifting power so that ideas are developed in local communities, to address their own needs. This requires systems and processes of knowledge production that are not vulnerable to external interests. Because these interests are usually leveraged through foreign investment, localisation can only be achieved by breaking the reliance on international research funding. Clearly, local financing is a political decision that each country must make independently – do they encourage home-grown knowledge production or continue relying on international organisations? Enhancing the demand for local knowledge requires cultural and societal change to overcome the deficit mindset.’

Development of publishing options for researchers in under-represented populations and groups.

An example of this is a coalition led by the West and Central African Research and Education Network (WACREN). The aim is to build both capacity for peer reviewing among African Public Health researchers though online courses and the development of new open publishing options through repositories for preprints and open reviews.

Creation of educational resources.

There is considerable activity in building capacity for the creation and use of Open Educational Resources (OER) - a key component for distributing education more widely as we discuss in a later section of this course. As an example, one of the recommendations of a UNESCO report includes: ‘developing the capacity of all key education stakeholders to create, access, re-use, re-purpose, adapt, and redistribute OER.’ This is in the context of one of the report’s stated aims: ‘One key prerequisite to achieve SDG 4 is sustained investment and educational actions by governments and other key education stakeholders, as appropriate, in the creation, curation, regular updating, ensuring of inclusive and equitable access to, and effective use of high quality educational and research materials and programmes of study.’ [Note: SDG 4 relates to Sustainable Development Goal number 4 ‘Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all.’ While on the topic of SDGs, a plea has been made to broaden the knowledge base in an editorial titled ‘We urgently need multiple knowledges to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals’]

Of course the main aim of this course is to help develop capacity among academics and collaborative partners, through discussing the theory and practice of distributing both the dissemination of knowledge as well as the creation of knowledge.

-

Please reflect on the extent of any biases in knowledge creation in your own subject areas and how you might be able to stimulate knowledge creation to capture the voices of under-represented populations