Resources: quality and information

Resources: quality and information

Both the quality of care and useful information systems are important attributes of good health systems.

An important measure of the need for quality healthcare is the paper Mortality due to low-quality health systems in the universal health coverage era: a systematic analysis of amenable deaths in 137 countries, which finds: "15·6 million excess deaths from 61 conditions occurred in LMICs in 2016. After excluding deaths that could be prevented through public health measures, 8·6 million excess deaths were amenable to health care of which 5·0 million were estimated to be due to receipt of poor-quality care and 3·6 million were due to non-utilisation of health care. Poor quality of health care was a major driver of excess mortality across conditions, from cardiovascular disease and injuries to neonatal and communicable disorders."In 2018, a report Crossing the Global Quality Chasm: Improving Health Care Worldwide was released. As the report states. "Poor-quality health care around the globe causes ongoing damage to human health. In low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), between 5.7 and 8.4 million deaths occur each year from poor quality of care, which means that quality defects cause 10 to 15 percent of the total deaths in these countries. The resulting costs of lost productivity alone amount to between $1.4 and $1.6 trillion each year.

A move toward universal health coverage (UHC) is the central theme of global health policy today, but the evidence is clear: Even if such a movement succeeds, billions of people will have access to care of such low quality that it will not help them—and indeed often will harm them. Without deliberate, comprehensive efforts to improve the quality of health care globally, UHC will be largely an empty vessel."

The scope of the problem (from Crossing the Global Quality Chasm)

From the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2018

The report identifies:

SIX DIMENSIONS OF QUALITY HEALTH CARE

-

Safety: Avoiding harm to patients from the care that is intended to help them.

-

Effectiveness: Providing services based on scientific knowledge to all who could benefit, and refraining from providing services to those not likely to benefit (that is, avoiding both overuse of inappropriate care and underuse of effective care).

-

Person-centeredness:* Providing care that is respectful of and responsive to individual preferences, needs, and values and ensuring that these values guide all clinical decisions. Care transitions and coordination should not be centered on health care providers, but on recipients.

-

Accessibility, Timeliness, Affordability: Reducing unwanted waits and harmful delays for both those who receive and those who give care; reducing access barriers and financial risk for patients, families, and communities; and promoting care that is affordable for the system.

-

Efficiency: Avoiding waste, including waste of equipment, supplies, ideas, and energy, and including waste resulting from poor management, fraud, corruption, and abusive practices. Existing resources should be leveraged to the greatest degree possible to finance services.

-

Equity: Providing care that does not vary in quality because of personal characteristics such as gender, ethnicity, race, geographic location, and socioeconomic status.

*Although the report uses the term patient when referring to the recipient of clinical medicine services, the committee’s position remains that quality improvement requires emphasis on the person, to remind the reader that health is determined by circumstances far beyond the clinical setting.

The report recommends: "Improving the quality of health care will require investment, responsibility, and accountability on the part of health system leaders. This should be the daily work and constant responsibility of all health care leaders, including ministers of health. Embracing principles of transparency, accountability, continual learning, and health system−patient co-design, countries will need to work with patients to design health system strategies, policies, and clinical care delivery, as well as mechanisms for monitoring, evaluating, and reporting progress.

A systems thinking and person-centered approach should inform the redesign of health care systems, with a focus of the needs of the patient. It is crucial to examine each level of a health care system the environment, the organization, the front line care delivery, and the patient—and how they interact and either help or inhibit one another. Appropriate, meaningful metrics—including patient- and population-based outcome data—should be captured to understand quality of care and inform improvements.

Beyond commitment and strategy development, implementation is key. As countries move toward UHC, governments can use specific mechanisms, such as strategic purchasing or selective contracting, to only purchase services from health facilities that are providing high-quality health care."

Health systems of the future (from Crossing the Global Quality Chasm)

From the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2018

WHO has a large section on Patient Safety, defined as: "the absence of preventable harm to a patient during the process of health care and reduction of risk of unnecessary harm associated with health care to an acceptable minimum." The site goes on to discuss "An acceptable minimum refers to the collective notions of given current knowledge, resources available and the context in which care was delivered weighed against the risk of non-treatment or other treatment.

Every point in the process of care-giving contains a certain degree of inherent unsafety.

Clear policies, organizational leadership capacity, data to drive safety improvements, skilled health care professionals and effective involvement of patients in their care, are all needed to ensure sustainable and significant improvements in the safety of health care."

Peoples-uni Open Online Courses includes a course on Patient Safety.

Information

Global Health Informatics "...emerged out of the broader biomedical informatics discipline as a distinct field focused on applying ICT to both public health and health care delivery in the context of low-to-middle income countries (LMICs). Its scope includes technologies that support the delivery of public and private health services (e.g., electronic health record, telemedicine, mobile health) as well as the management of health services across the care continuum within as well as across nations (e.g., health information exchange, health worker registries, epidemiology)." So you can see how important information is to supporting and strengthening health systems.

Pang et al challenged us: "to ensure that everyone in the world can have access to clean, clear, knowledge — a basic human right, and a public health need as important as access to clean, clear, water, and much more easily achievable". They go on to say: "Patients or consumers, healthcare professionals, and policymakers/managers who make up the health system must be better served by knowledge from various sources. If this is achieved, progress can be made in overcoming the seven ubiquitous health-care problems: errors and mistakes, poor quality health care, waste, unknowing variations in policy and practice, poor experience by patients, overenthusiastic adoption of interventions of low value, and failure to get new evidence into practice."

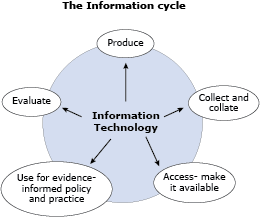

The graphic below, taken from another of the Peoples-uni Open Online Courses - Global Health Informatics - provides a framework for us to consider how information can be developed and used in the health system, and how Information Technology can support each step in the cycle.