Open access publishing

Résumé de section

-

We need to set this discussion in the context of the broader movement to open science.

The UNESCO definition of Open Science: ‘Open science is a set of principles and practices that aim to make scientific research from all fields accessible to everyone for the benefits of scientists and society as a whole. Open science is about making sure not only that scientific knowledge is accessible but also that the production of that knowledge itself is inclusive, equitable and sustainable.’

There are many components of openness, as described by UNESCO as Open Solutions: ‘Open Solutions, comprising Open Educational Resources (OER), Open Access to scientific information (OA), Free and Open Source Software (FOSS) and Open Data, have been recognized to support the free flow of information and knowledge, thereby informing responses to global challenges.’

As discussed in the Peer reviewing course, and emphasised here, ‘the history and political economy that allows some academic publishers to charge high fees and make extensive profits while academics provide much of the editorial and review functions without payment, has been well described...There are various categories of open access, and it has been estimated that since 2010, 47% of the 42 million published journal articles and conference papers are openly accessible, while 53% are behind a paywall, either requiring a subscription or pay per use, although there is an increasing trend towards open publication...Journal articles, as well as books and reports, may be published under a Creative Commons licence making them available for free use by others, subject to various conditions...there is widespread global support for the notion that publicly funded research should be freely available and not hidden behind paywalls. There are already many examples of publications of public importance being made freely available on a voluntary basis – such as many of the publications relating to the Covid-19 pandemic which have been published as open access for the public good. In addition to the philosophical issue of making publicly funded research freely available, there are claims that research citations are greater for open access articles than those requiring payment or a subscription.’

A major problem in the move towards open publishing of research papers is that journals make open publication dependent on the payment of Article Processing Charges (APCs). These can be as high as $9000 for a paper in Nature. This, of course, is a particular burden for those in low income settings and in the absence of rich institutions or research funders who are prepared to cover these publication costs. We note that the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation has now refused to cover these costs in their grants.

Hence the case for open repositories has been made, where researchers can upload their research, including the data on which the research is based. The allows open public access so that the results can be used by other researchers as well as policy makers. In addition, and as we discuss later, some repositories are linked to a review system to encourage reviews to be posted helping the paper to be improved and accepted by other publications.

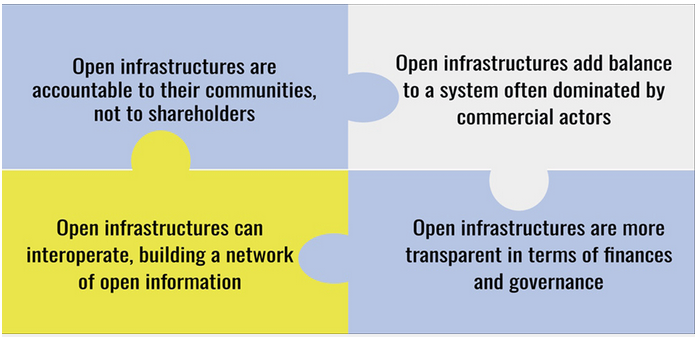

An editorial introducing a special collection Repositories transforming scholarly communication summarised this development nicely: ‘Digital repositories emerged in the 1980s to store and share research articles. In the early 2000s, the open access movement led to the creation of more digital repositories, including institutional repositories that allowed universities to share their research output with the public.’ The paper quotes the figure below in making the case for openness:

Figure: The importance of supporting open infrastructures for scholarly communications

There are a number of repositories in existence, and we list some of them later on.

Indexation and discoverability of research publications.

As mentioned in the Introduction to this course, the way that published research is indexed (and hence found through search engines) adds to the problem - the term bibliometric coloniality has been coined to refer to: 'the system of domination of global academic publishing by bibliometric indexes based in the Global North, which serve as gatekeepers of academic relevance, credibility, and quality. These indexes are dominated by journals from Europe and North America. Due to bibliometric coloniality, scholarly platforms and academic research from the African continent and much of the Global South are largely invisible on the global stage.' The authors propose a ‘process of dismantling bibliometric coloniality and promoting African knowledge platforms’ through ‘the creation of an African scholarly index’.

Central to this is the concept of Persistent identifiers (PIDs) ‘another crucial element of the scholarly communication ecosystem. PIDs serve as long-lasting references to digital objects, enabling easy and reliable access to research outputs of various types. PIDs can enhance the cohesion and discoverability of African scholarly content, ensuring that research remains accessible and traceable.’ Most will be familiar with Digital Object Identifiers (DOI) but there are others, such as Archival Resource Key (ARK) which has the advantage of keeping costs down as they can be implemented locally with open source tools.

Platforms and repositories

Digital repositories may be used to share the results of research and education. Here we are focusing on the use of repositories to publish preprints and in a later course we will cover their use to facilitate open reviews of these preprints.

The paper Next Generation Repositories from the Confederation of Open Access Repositories offers a good perspective on the importance of repositories.

Sciety aims "to grow a network of researchers who evaluate, curate and consume scientific content in the open." and offers repositories where evaluation of 'preprints' can occur.

eLife is eliminating accept/reject decisions after peer review and instead focusing on preprint review and assessment (more about eLife below).

PREreview (who we met previously for access to the resources they offer) is a platform providing 'ways for feedback to preprints to be done openly, rapidly, constructively, and by a global community of peers.'

medRxiv (pronounced "med-archive") is a free online archive and distribution server for complete but unpublished manuscripts (preprints) in the medical, clinical, and related health sciences. It provides a platform for researchers to share, comment, and receive feedback on their work prior to journal publication. Once posted on medRxiv, manuscripts receive a digital object identifier (DOI), so are discoverable, citable, and indexed by numerous search engines and third-party services. This is one of a suite of arXiv archives - 'a free distribution service and an open-access archive for nearly 2.4 million scholarly articles in the fields of physics, mathematics, computer science, quantitative biology, quantitative finance, statistics, electrical engineering and systems science, and economics.'

The Baobab repository has been developed in response to the need for an Africa specific repository. We will be using this to practice both the uploading of research papers as preprints, and of open reviews. Baobab uses the ARK identifier.

Focus on preprints

A good definition of preprints comes from the journal PLoS: 'A preprint is a version of a scientific manuscript posted on a public server prior to formal peer review. As soon as it’s posted, your preprint becomes a permanent part of the scientific record, citable with its own unique DOI.' The site goes on to show how to use preprints as a preparatory to submission to their journal.

eLife has an excellent summary of the reasons behind the preprint concept: 'The current science publishing system relies on a model of peer review that focuses on directing papers into journals. These reviews are not made publicly available, stripping them of their potential value to wider readers and leading committees to judge scientists based on where, rather than what, they publish. This can impact hiring, funding and promotion decisions, and highlights the need for a system of review that helps funding and research organisations assess scientists based on the research itself and related peer reviews.

Researchers globally are taking action to make science publishing and its place in science better, for example by preprinting their work and advocating for others to do so. This gives them greater control over their work and enables them to communicate their findings immediately and widely, and receive feedback quickly.'

You might also like to look at this from eLife: Scientific Publishing: Peer review without gatekeeping which describes why '..eLife began exclusively reviewing papers already published as preprints and asking our reviewers to write public versions of their peer reviews containing observations useful to readers' and that they 'found that these public preprint reviews and assessments are far more effective than binary accept or reject decisions ever could be at conveying the thinking of our reviewers and editors, and capturing the nuanced, multidimensional, and often ambiguous nature of peer review'. This approach is supported by the authors of Is Peer Review a Good Idea? from the viewpoint of the philosophy of science.

A provocative paper PreprintMatch: A tool for preprint to publication detection shows global inequities in scientific publication finds: ...that preprints from low income countries are published as peer-reviewed papers at a lower rate than high income countries (39.6% and 61.1%, respectively), and our data is consistent with previous work that cite a lack of resources, lack of stability, and policy choices to explain this discrepancy. They also found '...that some publishers publish work with authors from lower income countries more frequently than others.'Note: there are other suggestions of reviewer bias against journal submissions from the Global South: The role of geographic bias in knowledge diffusion: a systematic review and narrative synthesis. And North and South: Naming practices and the hidden dimension of global disparities in knowledge production.Here is another interesting idea: Preprint clubs: why it takes a village to do peer review where the authors (who are early career researchers in high income countries) describe turning their journal clubs into examining preprints and posting their analyses publicly. This could be replicable to include non-institutional and trans country online discussions.-

Reflect on your views on open access publishing and how this might be relevant in your own setting. Also, please comment on the posts of other participants.

Posting to this forum is a requirement for a certificate.

-